- Home

- Media Kit

- MediaJet

- Current Issue

- Past Issues

- Ad Specs-Submission

- Reprints (PDF)

- Photo Specifications (PDF)

- Contact Us

- PRIVACY POLICY

- TERMS OF USE

![]()

ONLINE

![]()

ONLINE

Sprint to the Finish

Editors’ Note

David Rubenstein is Co-Founder and Co-Chairman of the Board of Carlyle. Previously, he served as Co-Chief Executive Officer of Carlyle. Prior to forming Carlyle in 1987, Rubenstein practiced law in Washington, DC with Shaw, Pittman, Potts & Trowbridge LLP (now Pillsbury Winthrop Shaw Pittman LLP). From 1977 to 1981, he was Deputy Assistant to the President for Domestic Policy. From 1975 to 1976, he served as Chief Counsel to the U.S. Senate Judiciary Committee’s Subcommittee on Constitutional Amendments. From 1973 to 1975, Rubenstein practiced law in New York with Paul, Weiss, Rifkind, Wharton & Garrison LLP. Among other philanthropic endeavors, Rubenstein is Chairman of the Boards of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts, the Council on Foreign Relations, the National Gallery of Art, the Economic Club of Washington, and the University of Chicago, and serves on the Boards of Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, Johns Hopkins Medicine, the Institute for Advanced Study, the National Constitution Center, the Brookings Institution, the Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts, the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, and the World Economic Forum. Rubenstein serves as Chairman of the Harvard Global Advisory Council and the Madison Council of the Library of Congress. He is a member of the American Philosophical Society, Business Council, Board of Dean’s Advisors of the Business School at Harvard, Advisory Board of the School of Economics and Management at Tsinghua University, and Board of the World Economic Forum Global Shapers Community. Rubenstein is a magna cum laude graduate of Duke University, where he was elected Phi Beta Kappa. Following Duke, he graduated from the University of Chicago Law School, where he was an editor of the Law Review.

Firm Brief

Carlyle (carlyle.com) is a global investment firm with deep industry expertise that deploys private capital across three business segments: Global Private Equity, Global Credit, and Global Investment Solutions. With $381 billion of assets under management as of March 31, 2023, Carlyle’s purpose is to invest wisely and create value on behalf of its investors, portfolio companies, and the communities in which it lives and invests. Carlyle employs more than 2,200 people in 29 offices across five continents.

David Rubenstein and Sally Jewell, Secretary of the Interior,

examine repairs to the exterior of the Washington Monument.

Rubenstein donated $7.5 million for the refurbishment

following damage caused by an earthquake in 2011

Where did your interest in philanthropy develop?

When I was growing up, my parents did not really have any money so philanthropy was not a word that was spoken much in my house. The focus at that time was on making sure we could pay our bills every week. When Carlyle became successful, I had more money than I needed for my family and realized that I should do something more than just build a big bank account. I began to think about people and organizations that had been helpful to me and decided that I should start getting involved and giving back. It was really a recognition that, in the end, someone with modest financial means in the beginning of life and a long last name that is ethnic probably could not have been so successful and made significant money in many countries around the world. I wanted to give back to society and to the country that provided me with an opportunity.

How do you approach where to focus your philanthropic work?

There is clearly great need in many areas and I get approached all the time, but you can’t do everything. I set four standards for myself as I entered the latter years of my life, 20-plus years ago when I turned 50, as I am now 74. These standards are: I want to start something that otherwise would not get started; finish something that otherwise would not get finished; find something that I have an intellectual interest in so that I would not only be giving money, but also giving my time, energy and ideas; and find opportunities where I will likely see progress in my lifetime. These are the standards that guide my philanthropic work.

David Rubenstein announces a $10 million gift to build a

new visitor center at the Jefferson Memorial

in Washington, DC

When you mention getting involved in areas where you will see progress in your lifetime, does this relate to the concept you use about it being a “sprint to the finish?”

My father made it to 85 and my mother made it to 86, so I do not have genes that are likely to take me to my 90s. I am not the greatest physical specimen and I do not work out as much as I should, although I think about working out often. I want to get things done, and I have observed that as you age into your 60s, 70s, and 80s, the brain does not work quite as well and the body does not work quite as well. It is a struggle to see which is going to go first, your body or your brain. I use the term “sprint to the finish” as I am trying to get things done while I am able. You can never take life for granted. A friend of mine, Jim Crown, who was a leader in philanthropy, died recently in a car crash on a racing track in Colorado at the age of 70.

I do not want to slow down and smell the flowers, because at some point I will not be able to get things done the way I can now.

What led to the concept of “patriotic philanthropy” and what has made this such a major focus of your philanthropic work?

Many things in life happen by serendipity, and I think that some of the best things in life happen this way. When you were a young boy, you probably didn’t say that you wanted to run a magazine called LEADERS, and that you wanted to interview all these people in business and government. You kind of fell into it, and now you are really happy doing it and are very successful at it.

I didn’t say to myself that I was going to get involved in this area called patriotic philanthropy – what happened was that someone I knew told me that I should go to a viewing of the Magna Carta back in 2011, and when I got there I was told that it was not just a viewing, but that it was going to be auctioned the next night at Sotheby’s. The curator said that it would probably leave the United States after the auction, and I decided that I wanted to try to keep it in the United States, which is what happened when I bought it at the auction. The Magna Carta is now on long-term loan to the National Archives as a gift to the country and as a modest repayment of my debt to this country for my good fortune of being an American.

I was then approached by people about other important documents, such as the Declaration of Independence and the Emancipation Proclamation, and I started buying these documents to preserve them. Later, when the Washington Monument was damaged by an earthquake and it was clear that it would be difficult to get the funds from Congress to fix it, I decided to put up the money. This led to my involvement repairing other important buildings, such as the Lincoln Memorial, Monticello, the Arlington House Mansion at Arlington National Cemetery and Mount Vernon, among other sites.

Patriotic philanthropy is about doing things to remind people about the history and heritage of our country – to preserve documents that are important and to preserve buildings that are important. While you can go on the computer and see what is in these documents or look at these buildings, I believe that it is important for people to see the original document and actually visit the building because it reminds people about the country’s history. There are many problems the country is facing today, and I can’t solve most of them, but I want to contribute what I can to remind people about our history so that they are more informed citizens. Thomas Jefferson said, “An informed citizenry is at the heart of a dynamic democracy,” and unfortunately our citizenry is not well-informed about our history.

David Rubenstein announces an $18.5 million gift

to build a new visitor center at the Lincoln Memorial

in Washington, DC

Will you elaborate on your thoughts about the importance of studying and understanding history?

In the year 2000, the National Science Foundation conducted a study about whether we were falling behind in the sciences in competing with China, and the conclusion, not surprisingly, was that we were falling behind, which led to the creation of the acronym STEM. We decided that we needed to have more STEM education, and people became obsessed with the idea that if you did not have a STEM education, you would not be able to get a job, so the focus was on science, technology, engineering, and math. The social science people did not have a good acronym, and people started to believe that if they studied history, it would not help them get a job. The result is that history majors in the United States have gone from approximately 70 percent to around 2 percent today, which means people are not learning about history.

If you look at the degrees of people on Wall Street today, some studied STEM, but clearly not all. I think that you learn to think creatively and effectively problem-solve from studying the social sciences, but it has been an uphill battle getting this message out. The most popular major today at almost every university is computer science – when we went to college, this was not the case.

How do you focus your philanthropic efforts in education?

I think that as a parent, other than the love that you give to your child, there is nothing more important than an education. Every parent wants their child to be well-educated because when you have a good education, everything else is relatively insignificant. When you are Jewish and were chased out of Nazi Germany, if you had an education, you could rebuild your life.

I got a very good education in great schools because I was able to get scholarships, and I feel it is very important to help people who can’t afford school. I have tried to give back to the universities that I have been involved with, and to do it in a meaningful way with my money and my time. I received a scholarship to attend Duke University, and have supported Duke having served as chairman of the board. I received a scholarship to go to the University of Chicago and serve as chairman of the board of the school, and have also given them a substantial amount of money for scholarships to repay the scholarship and opportunity that they gave me. My two daughters went to Harvard, and I have been a large donor to Harvard, and have been a part of the Harvard Corporation for the past six years. I also support a scholarship program for the top high school students in Washington, DC. I want to help people get a good education and benefit from the value that a quality education provides throughout their lives.

David Rubenstein speaks at the unveiling of

the newly-restored U.S. Marine Corps War Memorial,

which he funded with a $5.37 million gift

Where did you develop your passion to support the arts?

I have been involved in Lincoln Center for more than 20 years, and for the past 13 years have been chairman of the Kennedy Center. I believe that the arts are very important since they give you a perspective that you don’t get in other subjects. If you look at other societies, such as in Asia, they usually want their children to learn the arts at a young age. Many young people learn to play a musical instrument because there is an understanding that these skills will help you in other parts of your life. Unfortunately, in our country, the first thing that gets cut in the school budget is arts education.

The arts are important for a few reasons: first, what is civilization about other than enabling people to express themselves in the way that the arts enable them to do, whether it be visual arts or performing arts; second, people who watch the arts learn and grow, and the arts make people happy. Happiness is one of the most elusive things in life – very few people are as happy as they would like to be – and one of the things that clearly makes people happy is the arts. Nobody leaves a performing arts center crying because they went there. Nobody leaves an art museum crying because they went there. People love the arts because it shows them how people can express themselves and provides ways for them to think about how to better express themselves too.

What about your commitment to support health?

There is not enough money that any human being has to dramatically change the way health is implemented in this world – it is such a gigantic problem. I have focused on diseases that I thought were not getting the money they needed, such as pancreatic cancer, which is a very deadly type of cancer. I created a pancreatic cancer center at Memorial Sloane Kettering. Another area is ALS, and I am working with Dan Doctoroff to support his effort leading Target ALS to figure out ways to eliminate ALS.

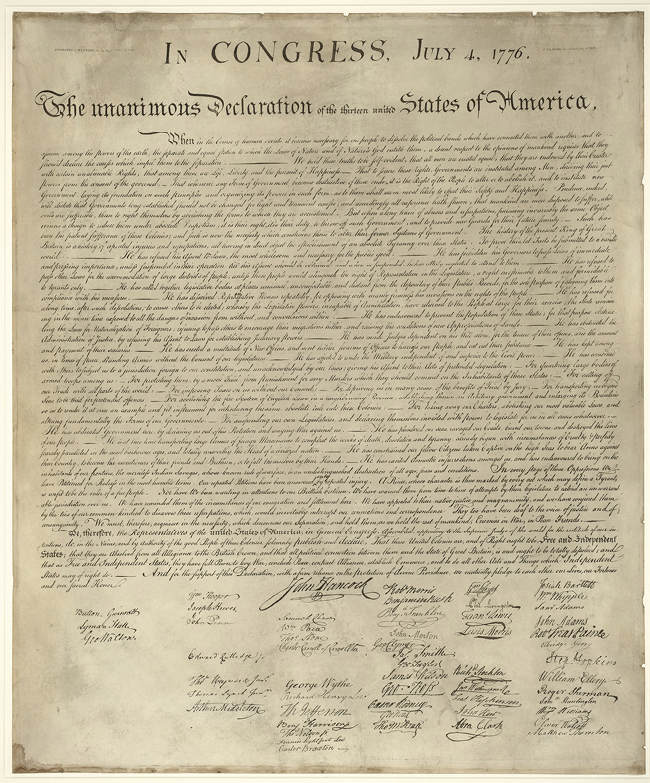

David Rubenstein has purchased several copies of the

Declaration of Independence (produced in 1823) and places them

on public display at prominent institutions including

the National Archives and the Smithsonian Institution

While much of philanthropy is focused on writing checks, you give your time, energy, and ideas to the causes you support. How important is it for your philanthropic activities be more than just about donating money?

The word philanthropy comes from an ancient Greek word that means loving humanity. It is not just about rich people writing checks. I believe that if you want to be a good philanthropist, give your time, energy and ideas, since they can be just as valuable as your money. The woman who created Teach for America, Wendy Kopp, did not have a lot of money, but she had a great idea. It is frustrating when they publish these lists of philanthropists by how much money they give – it should not only be about how much money was given.

You also commit your time to several television shows. What interested you in getting involved with television?

You clearly enjoy interviewing people because it allows you to meet different people and to test your wits against other people – it has an intellectual component to it. I remember when we were developing the show for Bloomberg, and Mike Bloomberg said that we would call it The David Rubenstein Show. I said that it was a long ethnic name that probably wouldn’t work, but he said it would be okay. It was easy to trust Mike since he has done pretty well with his name.

I am often amazed at how many people watch the show and assume that I am a full-time interviewer. People seem to like my style and I enjoy having the opportunity to meet different people and speak with people that I likely otherwise would not have a chance to do so. Heads of state, business leaders, or my most recent interview with Kim Kardashian, which is someone you have probably not even had a chance to interview yet.

I enjoy the show because I have to prepare for it which keeps my brain active and allows me to continue to learn.

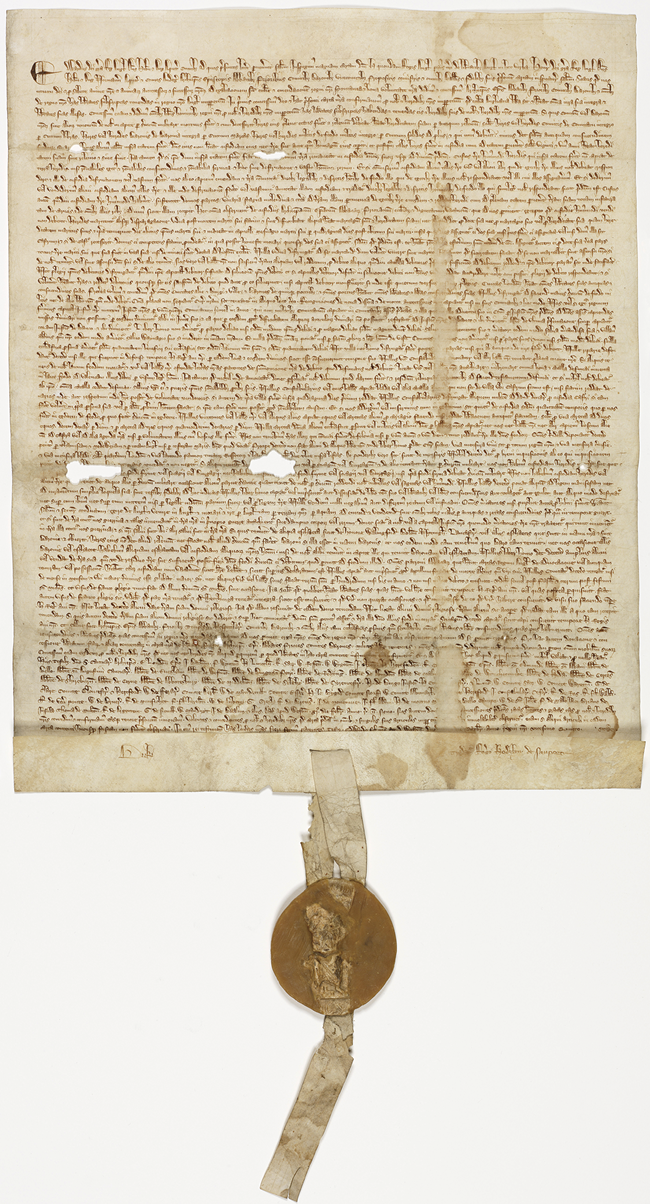

David Rubenstein purchased a 1297 Magna Carta

for $21.3 million and put it on permanent loan to

the National Archives

With all the success that you have achieved, how important has it been to never forget where you came from?

I grew up in a very small, Jewish area in Baltimore. I actually looked it up recently and our house was 800 square feet with two bedrooms and one bathroom. It was very modest, and I always like to remind myself of my roots because it shows that no matter where you come from in our country, you can do well. I did believe and I still do believe in the American Dream – sadly, many people in our country no longer believe in it. I sometimes drive back to my old neighborhood to see where I came from, and it makes me appreciate that I got lucky in life.

Do you think about your legacy?

I haven’t seen what the obituary writers at The Washington Post have written about me, but they have probably written something. I suspect, in the end, that patriotic philanthropy will get more attention than Carlyle because my approach to philanthropy has been unique while many people have built private equity firms. People can obsess about their legacy, but I don’t think about it too much. I am just trying to get things done and not do things that are going to embarrass my children.

My legacy will probably be my three children who are all pursuing what I call the highest calling to mankind – private equity – and hopefully part of my legacy will be helping them learn the business, and also setting an example for them about the importance of philanthropy.

When you reflect on the years building Carlyle, did you enjoy the process and are you able to appreciate what you accomplished?

At the time, I was in the middle of building it and did not realize it would be quite as successful as it became, and I keep thinking about all the mistakes I made – not all of the successes. When we started out, I remember telling the leasing agent that I only wanted 5,000 square feet since we were never going to have more than ten people in the firm, which obviously changed. I always think about how I could have made Carlyle so much better if I did not make certain mistakes, since I am not someone who likes to pat themselves on the back – my focus is on how I could do things better.

How do you define success?

If your parents are alive and they are proud of what you have done, that is success. What is life all about other than seeing your children be successful? My parents were alive to see much of what I accomplished, which was one of the great pleasures in my life.

Success is making other people feel that you have done something useful with your life. We are only on the planet for a relatively short period of time, and I think you want to do something that justifies your existence. No one really knows why they were put here, but you feel better if you know that you did something that makes humanity a little better. Success to me is about contributing to other people.

Did you know early in life that you had an entrepreneurial spirit and desire to build your own company?

I did not really know what an entrepreneur was. My goal in life was to be a lawyer, and to go into government and politics and work in The White House. I started that path when I was in my 20s – I did not think about business or making money. If you look at most people who have been successful at building a company, they were not focused on making money, but rather about making their idea work. When I was growing up, the entrepreneurial environment that we now have didn’t exist.

What were the keys to Carlyle’s success?

We were different because we were based in Washington and people thought about us a little differently. We did not have an investment banking background, which brought a different perspective to what we did. The thing that really worked well was that we had a concept that is common today, but was novel at the time – to be more than a buyout firm. Carlyle was a firm that had many different types of private equity investments – buyout, venture capital, growth capital, real estate – and was a global firm having separate units in Asia, Japan, the Middle East, and so forth. The niche we came up with was to build a multi-discipline, global investment firm, which had not existed at that time.

What advice do you offer to young people beginning their careers?

I tell young people to experiment. Try different things – I did not start Carlyle until I was 37 years old. Find something you are passionate about – to be successful you need to love what you do. Make a difference – contribute to humanity in some way.![]()