- Home

- Media Kit

- MediaJet

- Current Issue

- Past Issues

- Ad Specs-Submission

- Reprints (PDF)

- Photo Specifications (PDF)

- Contact Us

- PRIVACY POLICY

- TERMS OF USE

![]()

ONLINE

![]()

ONLINE

Becoming the

Change You Want

Editors’ Note

As one of the preeminent civil rights leaders of our time, Reverend Al Sharpton serves as the founder and president of the National Action Network (NAN), anchors Politics Nation on MSNBC, hosts the nationally syndicated radio shows Keepin’ It Real and The Hour of Power, holds weekly action rallies and speaks out on behalf of those who have been silenced and marginalized. Rooted in the spirit and tradition of the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., NAN boasts more than 100 chapters across the country to promote a modern civil rights agenda that includes the fight for one standard of justice, decency and equal opportunity for all.

Sharpton started his ministry when he was just four years old, preaching his first sermon at the Washington Temple Church of God and Christ. At the age of 13, he was appointed by Rev. Jesse Jackson and Rev. William Augustus Jones as Youth Director for the New York chapter of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference’s Operation Breadbasket, an organization founded by Dr. King in 1966. Operation Breadbasket served as the economic arm of SCLC and provided the curious and vivacious Sharpton with on-the-ground training in civil disobedience and direct action. Sharpton had the unique opportunity to absorb a wealth of knowledge from Dr. King’s lieutenants: Rev. Jones, Rev. Ralph Abernathy, Hosea Williams, and later Dr. Wyatt Tee Walker. He would go on to incorporate Dr. King’s teachings of nonviolent activism into his work and fight for justice. At the age of 16, he founded the National Youth Movement, Inc. and in 1991 officially launched National Action Network. Sharpton is the author of several books, including Go and Tell Pharaoh, Al on America, The Rejected Stone, Rise Up, and most recently, Righteous Troublemakers. He has served as a guest lecturer at Tennessee State University, and has received honorary doctorate degrees from Medgar Evers College, Fisk University, Bethune-Cookman University, Virginia Union University, Voorhees College, among others.

Organization Brief

National Action Network (nationalaction.network) is one of the leading civil rights organizations in the nation with chapters throughout the entire United States. Founded in 1991 by Reverend Al Sharpton, NAN works within the spirit and tradition of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. to promote a modern civil rights agenda that includes the fight for one standard of justice, decency and equal opportunities for all people regardless of race, religion, ethnicity, citizenship, criminal record, economic status, gender, gender expression, or sexuality.

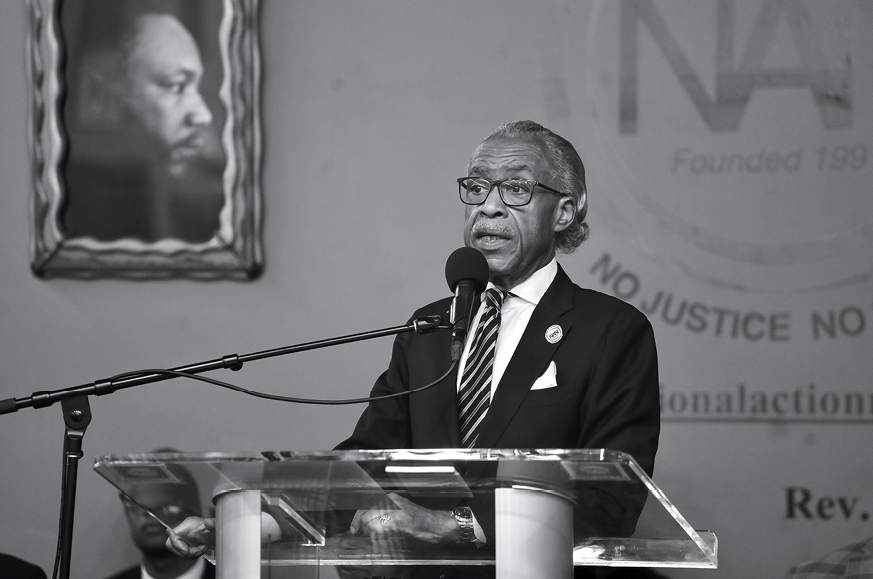

Reverend Al Sharpton speaking at the House of Justice

Rally in Harlem, New York in May 2023

Will you highlight your career journey?

I started as a boy preacher in the Pentecostal Church in Brooklyn, New York. I preached my first public sermon when I was four years old to about 900 people, and by the time I was seven, I went on the circuit in the Pentecostal Baptist Black churches in the New York area as the Wonder Boy preacher. By the time I was 12, I had become very enticed with watching the news. My father left when I was 10, so I didn’t go out a lot and play with other kids because we moved from a middle-class neighborhood in Queens to projects in Brooklyn and I was trying to adjust to a new environment. As I watched the news a lot after school, I fell in love with the image of Adam Clayton Powell. I convinced my mother to let me go up to his church and meet him. To my surprise, he knew who I was from being a boy preacher. I became totally enthralled with doing social justice ministry like Powell, who was a congressman but had been an activist and civil rights leader. My mother, who was a strict, fundamental Pentecostal Church member, fearing that I was going to leave the church, took me to our Bishop, Bishop F.T. Washington. He brought me to someone he knew who lived in the same neighborhood, Reverend Dr. William H. Jones, who led the chapter of Martin Luther King’s Organization in New York. So, the Christian Leadership Conference’s Operation Breadbasket and our Dr. Jones decided to make me their youth director so I wouldn’t leave the church. Operation Breadbasket recruited a lot of young people to participate in picketing and marching and the like. I became youth director of Greater New York Operation Breadbasket. I met Reverend Abernathy, who had taken over the organization that year because Dr. King had just been killed that April, and I met the head of Breadbasket, Reverend Jesse Jackson – the rest is history.

How did your childhood and early years impact your life’s work?

I think it impacted my life’s work by being born of parents who were middle class, entrepreneurial Blacks from the South. I was born and raised in Brooklyn. My father owned the house we lived in and owned other houses as well as a corner store. I spent Saturdays with him riding around, collecting rent from his other buildings. The four of us in the family then moved to a nice corner house in Queens. My father would buy a new Cadillac every year. Then, all of a sudden, he left. He walked out on us, abandoned us, and I found myself living for a few months in Albany projects and then in a tenement in Brownsville. So, I got to know the difference in zip codes, the difference in how you were treated based on where you live, and the difference in race. I think that’s what impacted me to spend the rest of my life fighting for equality and fairness no matter what peoples’ economic background might be or what geographic location they lived in. So, the impact of these experiences at a very young age gave me the course of where I went in life.

What was your vision for creating the National Action Network and how do you define its mission?

I had been involved from Operation Breadbasket when I was 12 years old, all the way through my late 30s, in various movements and various activities where I became pretty well known in the New York region, and then was going national, and at one point I got in a conflict with the people in the organization. I was stabbed in '91 leading a march in a section of Brooklyn called Bensonhurst, where a young man, Yusuf Hawkins, 16 years old, had been killed by a mob that said they didn’t allow Blacks in the neighborhood. I would go out and lead marches – several hundred people in the neighborhood every week – saying to the people in that area: you know who killed this young man, you know who shot him – give him up. After weeks of protest, we got them to give up some – not the rest – and we kept marching. I was stabbed in my chest leading one of those marches by one of the guys in the neighborhood. As I lay in the hospital, not knowing how serious the wound was, I said that I really needed a defined organization pursuing the principles of Dr. King, because even though we were marching and doing King-like things, I wanted to create an organization based on Dr. King’s principles. This is how I started. So, when I got out of the hospital, where we were having rallies, many decided that they didn’t want to allow whites in the rallies anymore. That was against my principles and I left and went to Harlem – even though I lived in Brooklyn and had shaped the rallies in Brooklyn – to form National Action Network on the principles of Dr. King and non-violent direct action. I didn’t fall out with those I left since all of us wanted justice and fairness, but our tactics were different. Mrs. Coretta Scott King always said to me that you must become the change you want.

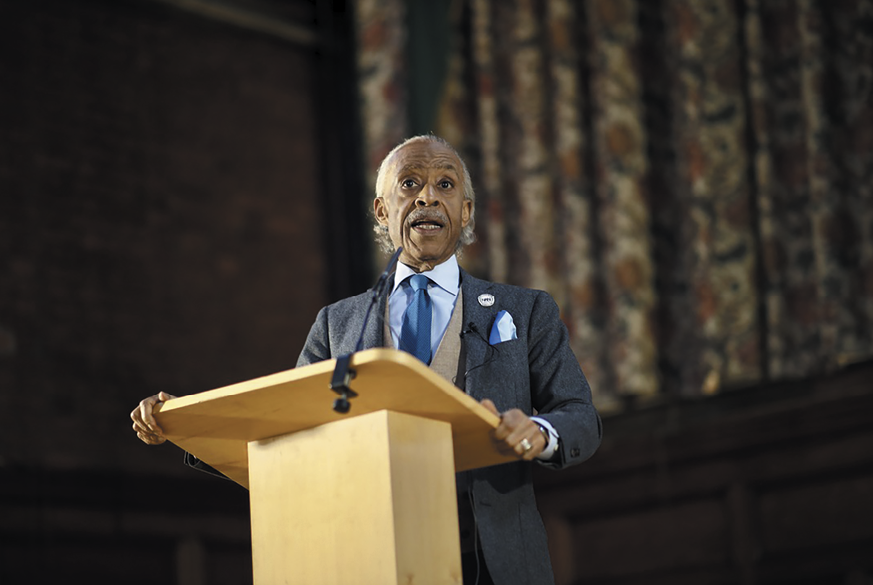

Reverend Al Sharpton speaking at University

of Cambridge London in February 2023

How has NAN evolved over the past 30 years?

NAN started having Saturday rallies every Saturday morning in a schoolhouse in Harlem. We started with about $200 in our pocket. We went from there to getting our own headquarters where we have our Saturday rallies and staff. We now have a staff of 73 people, headquarters in New York and offices in Los Angeles, Washington, DC, Atlanta, Miami, Detroit, and a tech center in Newark, New Jersey. We have between an $8 and $11 million annual budget with no federal, state and city funds, so we’re free to do whatever we want. Our National Convention has had every major Presidential candidate, had President Obama twice while he was president, and President Biden has spoken for the organization. We have been able to impact policies, ending stop-and-frisk in New York, helping get an actual mandate to end it. We were key in making no chokehold laws a state law, creating racial profiling laws in the early '90s when we fought a case in New Jersey that led to New Jersey making racial profiling laws that other states duplicated. We were involved in the effort to have private sector corporations target a certain amount of their contracts to go to Blacks and Latinos.

When George Floyd occurred, we were one of the lead groups involved and I did the eulogy at his funeral. We proposed the George Floyd Justice and Policing Act, and while we couldn’t get it through Congress, we got the President to sign an executive order. National Action Network has had, probably over the last 30 years, the most continuous demonstrations of public protests on a consistent basis – in the Ahmadou Diallo case, we had 11 consecutive days of civil disobedience. Over the last 30 years, NAN has been on the vanguard of doing that, and I don’t think any group has done what we do with direct action, but it’s always connected to state or city policy laws changing, which was the Martin Luther King way of doing things.

Will you discuss NAN’s work in addressing criminal justice reform?

NAN’s work in criminal justice reform is focused on having police reform where police do not operate without accountability, where they do not become the judge, jury, and executioner. They must not become criminal to fight crime – we support police fighting crime, but they cannot become criminal. We support diversity in police departments. We encourage Blacks and Latinos and Asians to join the police force.

There is no reason to choke someone to death. There’s no reason to stop and frisk 80-90 percent in the Black community and not in other communities. There is no reason to target people for prosecution based on who they are in terms of their race or their economic standing.

Addressing criminal justice has been our signature work and we’ve gotten results.

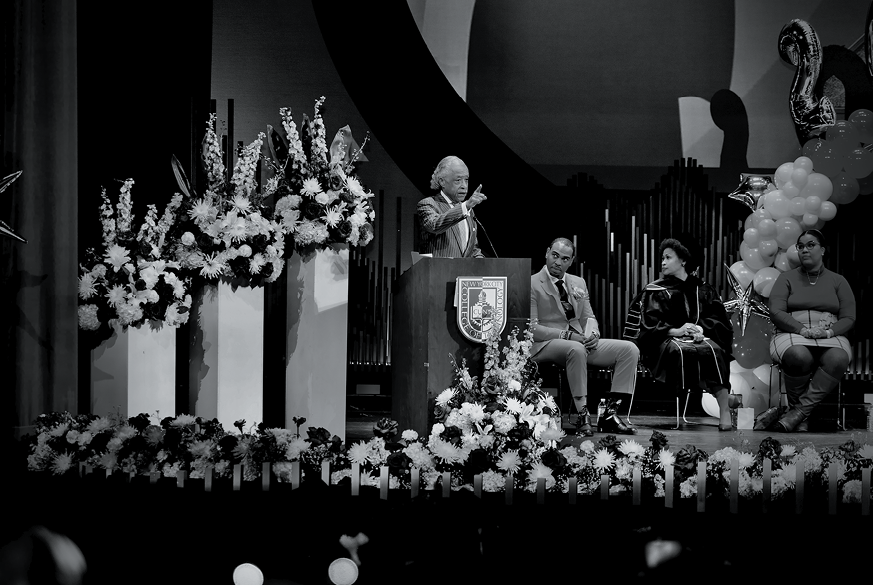

Reverend Al Sharpton delivering the commencement address for

Brooklyn Laboratory Charter School’s Graduation in June 2023

How is NAN working to impact voting rights and ensure that every vote in every community across the nation is counted?

Well, I think that one way is the John Lewis Voting Rights Act that we’ve been critical in supporting and advancing, and the other is in our state-by-state chapters. We have 127 chapters. We have fought to make sure state laws are enacted, like in Georgia, where they tried to say you could not serve beverages while people are standing on line waiting to vote. So, it’s a step-by-step process that we’ve been on the forefront of, and we will continue to fight to get the John Lewis bill passed, and in the interim will work state-by-state with our chapters on the ground.

Will you highlight NAN’s efforts around corporate responsibility as well as diversity and inclusion?

We’ve been at the forefront of saying to major corporations that you ought to have targets that you want to achieve on how many people of color – Black, Latino, Asian – are employed. How are they situated in terms of the corporate ladder? Is your C-suite diverse? Is your board of directors diverse? Who are your contractors? The leverage we use is saying to companies, if you get 20, 30, 40 percent of your consumer dollars from Black and brown communities, then you ought not hesitate to reflect that in how you do business.

How is NAN investing in youth leaders and putting youth at the forefront of the movement for civil rights?

I’m very sensitive about this since I started at 12 years old and became Youth Director of New York Breadbasket at 13. I am sensitive to the point where on our national staff and of all officers, I would say at least 85 to 90 percent are under 45 years old, and most are in their 30s. The way for young leaders to grow is by learning on the field – you can’t teach civil rights in a college classroom. This past August, we took over 150,000 people to Washington for the 60th anniversary of the March on Washington. Young people on my staff were able to get 16 HBCU student groups – young people – to come to the March and they spoke on the program. The first two hours of the program they conducted and I didn’t even come out until it was over. It is like teaching somebody how to swim by throwing them in the water. Our chapters are led by young people and I am a firm believer that the movement has to continue to the next generations because it won’t be solved in my lifetime. I was mentored by Reverend William Jones, Reverend Jesse Jackson – I was 13 to 15 years younger than them, and I am very sensitive to those 15 years younger than me and want to provide them a platform to be able to develop their leadership skills.

Will you provide an overview of NAN’s Newark Tech World and its work to bridge the digital divide?

NAN Tech World was started in New Jersey by Reverend Bartley, who wanted to have a center that would teach young people and seniors how to code and how to use technology. You would be surprised at the number of people in our communities that don’t know how to deal with an iPad or laptop. The Center was set up to provide training sessions. Reverend Bartley was able to get private corporations to help finance the Center, and the city of Newark is a partner. There is a tech mobile where you can go on a bus and there are laptops that we teach you how to use. It has been very successful.

What do you feel are the keys to effective leadership?

Leaders must have a vision and they must have the determination to stay on track with that vision, as opposed to reacting to what is popular. Martin Luther King Jr. said that there are two types of leaders – there are thermostats and there are thermometers. Thermometers judge the temperature in a given space – thermostats change the temperature. I’m in the thermostat tradition. I believe in turning up the heat or turning it down based on what is needed at the time, and not going by what is popular, It is about going by what is right. Real leaders don’t respond to public opinion – they help to shape it.

When I started at 12 years old, we could not imagine that there would be a Black President or a Black Vice President. When I spoke at the March on Washington, standing where Martin Luther King Jr. spoke 60 years earlier, I thought about how there was a Black woman Vice President of the United States. Dr. King never dreamed that would happen. We elected and reelected a Black President. There have been Black CEO’s of major corporations, Fortune 500 corporations, Black billionaires.. However, we still have the black/white wealth gap; we still have Black unemployment, usually double that of white unemployment; the educational data for Blacks is less than whites in terms of where we are and our ability in mathematics, history and languages; in the health area, we still are #1 in many of the infirmities that plague this country.

There has been some progress, but we also have a long way to go. NAN and I are committed to try to close as much of that gap as possible. Our job is to run the lap and let those behind us run the next lap. I am determined to use the things that Reverend Jones and Reverend Jackson and others put in me to run my lap as strongly as I can, and trust that the young folks that come behind me will pick up the baton and run the next lap.

How do you define success?

Success is having specific, clear goals in mind. I want to build a structure and organization that will be financially stable and outlast me. It’s like the successful mountain climber. I talked to Dr. King about getting to the mountaintop. What happens when we get to the mountaintop? He said, “we get to the top of the mountain, look over, and there’s always a mountain taller than the one you’re on. Go down the mountain you’ve conquered and start climbing the higher mountain. You’ll never run out of mountains to climb.”

What advice do you offer to young people growing up during these uncertain and volatile times?

In this time of uncertainty, you ought to first be certain what you want to do, who you want to be, envision it, and get up every morning with that vision in mind. I believe that what you see is what you can become – don’t let the noise, your environment, or anything else deter you from who you see yourself becoming. I had friends when we were in our 20s and used to say, “I want to be this, or I want to be that.” One wanted to be the next Black mayor of New York, and another wanted to be a member of Congress. I wanted to build a civil rights movement nationally, like Dr. King’s movement. And 20 years later, the one that wanted to be the next Black mayor, had become the first Black governor, David Patterson. The one that wanted to be a member of Congress, Greg Meeks, became a senior member of Congress, and is the Ranking Member of the House Foreign Affairs Committee. I’ve built the National Action Network. When we were dreaming it, it made no sense. People looked at us like we were crazy, but I think the more people that are against you, the more fuel it gives you to make it happen. I think the test is when nobody can see what you see. Leaders don’t try and gain the approval of others. Leaders do things where nobody saw a possibility, and make it possible. That’s what distinguishes you from the crowd.![]()