- Home

- Media Kit

- MediaJet

- Current Issue

- Past Issues

- Ad Specs-Submission

- Reprints (PDF)

- Photo Specifications (PDF)

- Contact Us

- PRIVACY POLICY

- TERMS OF USE

![]()

ONLINE

![]()

ONLINE

Representing Everything Theatrical And Glamorous About New York

Editors’ Note

Peter Gelb’s career has followed a singular arc that began with his teenage years as an usher at the Metropolitan Opera and led to his appointment, in August 2006, as the storied company’s 16th general manager. Gelb has been at the forefront of the artistic world throughout the tumult of the past four years, bringing the country’s largest performing arts organization back from the brink after the pandemic closure, leading the way in commissioning and presenting new works, and rallying artistic forces in defense of Ukraine – including a benefit concert at the Met shortly after Russia’s invasion and, in partnership with the Polish National Opera, the launch of the Ukraine Freedom Orchestra which brought together leading Ukrainian musicians from around the world for international tours in summer 2022 and 2023, under the leadership of Canadian-Ukrainian conductor Keri-Lynn Wilson. Now in his 18th year at the helm of the Met, Gelb has overseen a number of initiatives aimed at revitalizing opera and connecting it to a wider audience since the start of his tenure. He has also made a priority of revitalizing the repertory with commissions of numerous new works and new productions of both classic operas and modern masterpieces, overseeing more than 85 new stagings by some of the world’s greatest opera and theater directors. Gelb created The Met: Live in HD, a Peabody and Emmy Award–winning series of live performance transmissions shown in high definition in movie theaters. The series has sold more than 31 million tickets since its inception in December 2006 and is currently seen in more than 70 countries across six continents. As an award-winning producer of films, recordings, radio broadcasts, telecasts, concert events, operas, and festivals, he worked with many of the world’s leading artists prior to becoming Met General Manager. As president of CAMI Video, a division of Columbia Artists Management that Gelb founded in 1982, he served as executive producer of the Met’s television series for six years, producing 25 televised presentations for the company. His productions have earned 13 primetime Emmy Awards as well as multiple Peabody Awards. From 1995 until joining the Met, Gelb was President of Sony Classical, one of the largest international classical record labels, which he led through a period of notable growth and creativity.

Institution Brief

The Metropolitan Opera (metopera.org) is a vibrant home for the most creative and talented singers, conductors, composers, musicians, stage directors, designers, visual artists, choreographers, and dancers from around the world. The Metropolitan Opera was founded in 1883, with its first opera house built on Broadway and 39th Street by a group of wealthy businessmen who wanted their own theater. Today, the Met continues to present the best available talent from around the world and also discovers and trains artists through its National Council Auditions and Lindemann Young Artist Development Program. Almost from the beginning, it was clear that the opera house on 39th Street did not have adequate stage facilities, but it was not until the Met joined with other New York institutions in forming Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts that a new home became possible. The new Metropolitan Opera House, which opened at Lincoln Center in September 1966, was equipped with the finest technical facilities. Each season, the Met stages more than 200 opera performances in New York. More than 800,000 people attend the performances in the opera house during the season, and millions more experience the Met through new media distribution initiatives and state-of-the-art technology.

Anthony Roth Costanzo in the title role of Philip Glass’

“Akhnaten” performed at the Metropolitan Opera

When did you develop your interest and passion for classical music?

Growing up in New York, my father was a drama critic and my mother was a writer and the niece of the legendary violinist, Jascha Heifetz. I was taken to the theater and concerts from a very young age. When I was 13, my parents brought me with them when they were invited to the Met to sit in the box of Rudolf Bing, then the Met’s aristocratic General Manager. During the performance of Carmen, with African American soprano Grace Bumbry in the title role, two hecklers in an adjacent box booed Bumbry’s performance of the “Habanera.” Furious, Bing leaped to his feet and threw them out. I was impressed.

When I was 16 and a junior in high school, my father persuaded the Met to hire me as a part-time usher. My station was in the family circle standing room, the nosebleed section at the very top of the Met’s auditorium, where I had my first exposure to some of the Met’s most devoted fans who would often fight with each other over their favorite singers. My job was to break up the fights or to call in reinforcements.

From my vantage point at the very top of the Met, more than a hundred feet from the stage, I listened to the glorious voices of the greatest singers of 1970 – a golden era for operatic voices; the legendary Leontyne Price, perhaps the greatest Aida of all time; Renata Tebaldi, Italy’s number one diva and Maria Callas’ main rival for the title of Prima Donna Assoluta; and Franco Corelli, the forerunner to Pavarotti as the world’s greatest tenor, but whose severe episodes of stage fright tragically foreshortened his career. All this had a magical effect on my teenage soul. From the impressive gold proscenium that framed the stage to the sea of plush red velvet seats, the Met seemed to represent everything theatrical and glamorous about New York. It was as if all the performing arts had been rolled into one gold-leafed operatic palace. This is when I fell in love with the Met and it’s why, five decades later, I’m committed to never letting it down.

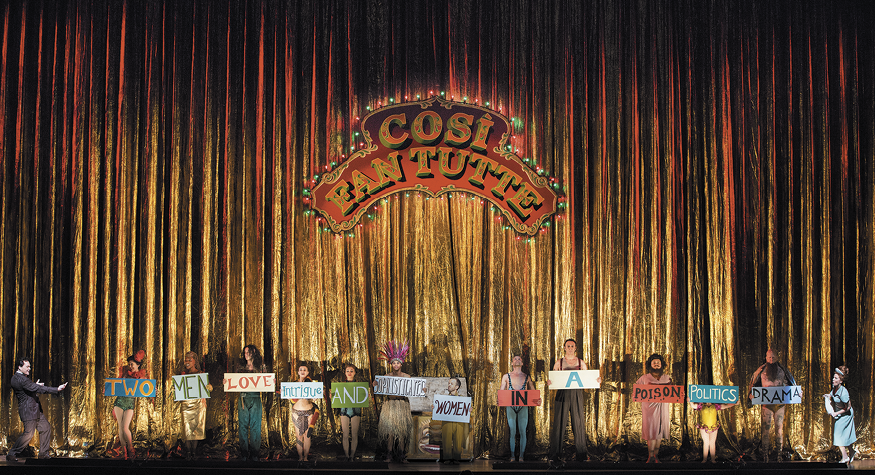

A scene from Act I of Mozart’s “Così fan tutte”

Will you discuss your career journey?

Upon graduating from high school, I went to work as an office boy for Sol Hurok, a leading impresario who persuaded the pianist Arthur Rubenstein, Vladimir Horowitz’s principal rival, to change his first name to “Artur” to help make him more appealing at the box office. Hurok once said, “if the people don’t want to come, you can’t stop them.”

When I was in my 20s, I was the Assistant Manager of the Boston Symphony Orchestra and was responsible for initiating and organizing its historic tour to China in 1978. The tour to China was a cultural and political event to celebrate the resumption of relations between the U.S. and China. Jointly announced by Deng Xiaoping and Jimmy Carter on the stage of the Kennedy Center in Washington, DC, the Boston Symphony tour of China marked the end of the Cultural Revolution, following the imprisonment of the infamous Gang of Four.

Eight years later, in 1986, I was the 33-year-old manager of Vladimir Horowitz, arguably the greatest pianist in history and perhaps its most neurotic. I brought him to Moscow in official recognition of the pending détente negotiated by Gorbachev and Reagan. Horowitz’s concert was presented live and in its entirety as a news special on CBS in the United States and on the BBC.

Getting Horowitz to agree to return to his motherland was extremely challenging, since his many phobias had to be addressed to his satisfaction. Obsessed with his diet, Horowitz insisted on eating the exact same menu for breakfast, lunch, and dinner for years on end. At the time, his nightly meals included fresh Dover Sole and asparagus, two items decidedly not available in Cold War Moscow. Unfazed by this culinary challenge, Secretary of State George Schultz and the American Ambassador to Russia, Arthur Hartman, enlisted the aid of our allies. The Italian Ambassador promised to secure the asparagus and the British Ambassador arranged for fresh Sole to be air couriered from London. Thus, the first Dover Sole airlift to Moscow was born.

To make Horowitz feel at home, the Hartmans moved out of their own master bedroom suite in Spasso House, the American Ambassador’s palatial residence in Moscow, temporarily giving it to Horowitz and his wife, Wanda, the temperamental daughter of Arturo Toscanini. I was assigned the principal guest bedroom – the same yellow room that Kissinger stayed in when he would visit.

“Since the Met is the world’s leading opera company, the future of opera relies on the Met to succeed - and we’re dedicated to achieving that goal.”

One month before the Horowitzes were supposed to arrive with an entourage that included his chef, piano tuner, his customized trigger action Steinway, and me, disaster struck. The pianist Vladimir Feltsman, one of the Jewish Refuseniks who were endlessly waiting for their exit papers, was about to begin a recital in the salon of Spasso House, when it was discovered that the strings of his piano had been cut. In the audience was The New York Times bureau chief, who filed a front-page article about what clearly had been an act of KGB sabotage. Horowitz read the article and immediately threatened to cancel. It was only when Reagan himself had a letter hand-delivered on White House stationery to Horowitz guaranteeing his safety and the safety of his piano, that the tour was back on. In fact, Horowitz’s piano traveled to Moscow guarded by U.S. marines.

Managing Horowitz was challenging, but also thrilling, and he was always ready to offer me his own homespun advice. With regard to acoustics, he told me, “If the check is good, the acoustics are good.” He also advised me to read menus from right to left – “Like Hebrew,” he explained. Throughout my career, I’ve pursued politically charged cultural events, whether in China or Russia, no matter how tense, since art always has had the possibility to transcend politics and to soothe relations. In 1990, I produced Tchaikovsky’s televised 150th birthday concert from St. Petersburg, bringing with me Itzhak Perlman, Yo-Yo Ma and Jessye Norman, her suitcases stuffed with turkey, since food rationing in St. Petersburg had just begun.

In 1991, I co-directed a documentary film about Mstislav Rostropovich and Galyna Vishnevskaya. It was a portrait of their heroism in the face of Soviet persecution. Ten years earlier, they had stood up to Brezhnev, sheltering Alexander Solzhenitsyn in their dacha outside of Moscow, even though it meant sacrificing their careers as Russia’s leading cellist and soprano. Facing global criticism for his mistreatment of them, Brezhnev chose to exile them rather than send them all to the gulag. Our film was about their triumphant return during Perestroika, a time when it looked like the world might be coming together. But of course, Putin has completely reversed that trajectory.

In 1997, when I was running the Sony Classical record label, we joined the Hong Kong government in commissioning Tan Dun to compose the official music of the Handover, “Symphony 1997,” featuring Yo-Yo Ma and ancient Chinese bells. At the time, the world was hopeful that China would keep its word.

These are some of the experiences that prepared me for my work as the 16th General Manager of the Met, the largest and most challenging nonprofit performing arts company in the world.

The Metropolitan Opera’s General Manager Peter Gelb

and Music Director Yannick Nézet-Séguin

How do you focus your efforts as general manager of the Metropolitan Opera?

When I signed my Met contract back in 2004, it included a clause (and still does) that I have to be available 24/7, since you never know what might happen in the daily and nightly events of the world’s busiest, and sometimes wackiest, performing arts company.

In reaction to our production of COSI, set in Coney Island in the ’50s, with real life circus sideshow performers, including sword swallowers, fire breathers, and a snake charmer, one of our stagehands said, “I always thought the Met was a circus. Now it really has become one.”

At the Met, anything can happen, and often does. There was the performance of Mussorgsky’s masterpiece Boris not so long ago in which the bass baritone Yevgeny Nikitin was performing the role of Rangoni on a night when the great bass Rene Pape, singing the title role of Boris, was not feeling well. Pape began the evening’s performance, but just before the final and famous Boris death scene, Pape decided backstage that he couldn’t carry on. With two minutes to go before his entrance, we stripped off his costume and wig and threw them onto Nikitin, who had left the stage moments earlier dressed as Rangoni, one of Boris’ tormentors. Not missing a beat, Nikitin reentered the stage, now dressed as Boris. He sang and died as Boris right on cue. As soon as he was carried off stage, he was quick-changed back into his Rangoni costume just in time for his entrance on horseback for the final tableau. After he rode off the stage and dismounted, we put him back into the Boris costume for the curtain calls, since by this time Pape had gone home. For those members of the audience who were feeling a little sleepy at this point late in the evening, they probably never noticed. For the members of our company, it was just another wild night at the opera.

What have been the keys to the strength and leadership of the Metropolitan Opera over the years?

During his 22-year reign at the Met, the second longest tenure of a General Manager at the Met in a history that dates back to 1883, Rudolf Bing used his position to fight against inequality and on behalf of social justice. He also did not suffer fools and was famous for his dagger-like quips. During a protracted labor negotiation, a union leader accused Bing of openly showing his disdain. Bing responded, “Actually, I’m doing my best to conceal it.” Bing was also known for his artistic feuds, with everyone from Maria Callas to the conductor Geroge Szell. When someone noted that Szell was his own worst enemy, Bing replied, “not as long as I am alive.”

Bing’s legacy as one of the great artistic leaders of the 20th century is enshrined in history. He was responsible for modernizing the Met and opera as an art form, bringing in Broadway directors, and sweeping away the cobwebs of theatrical inertia. An operatic Moses, he led the company from its antiquated old house on 39th Street and Broadway to the promised land of its new home at Lincoln Center in 1966.

According to my mentor, the late Ronald Wilford, who ran what at the time was classical music’s most powerful talent agency, Bing would playfully pretend to swat singers on his desk as if they were flies. And Bing kept a gavel on his desk as an accessory for ending meetings. His former secretary presented that gavel to me a few years ago and I keep it nearby, but I haven’t yet had occasion to use it.

Maestro Keri-Lynn Wilson with the Ukrainian Freedom

Orchestra at Damrosch Park, Lincoln Center,

on August 18, 2022

My immediate predecessor as General Manager was Joseph Volpe, who began at the Met as a stage carpenter before eventually taking over in 1990. Volpe was known for running the Met with an iron fist, once infamously telling the soprano Angela Gheorghiu, who had complained about the color of her wig, “your wig is going on, with or without you.”

Meanwhile, like Bing, I will continue to fight for what is right. That’s why the Met helped create the Ukrainian Freedom Orchestra in the days following the Russian invasion. My wife, the conductor Keri-Lynn Wilson, is its Music Director. Keri-Lynn is part Ukrainian and grew up in Winnipeg, a Ukrainian haven since the early part of the 20th century when waves of Ukrainian immigrants settled there. Under the patronage of Ukrainian First Lady, Olena Zelenska, the orchestra is made up of Ukrainian musicians from across the country who have come together each summer since the invasion to perform concerts across Europe and in the United States in defense of Ukrainian culture. Most recently, in commemoration of the second anniversary of the invasion, Deutsche Grammophon released their recording of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, with the final choral movement sung in Ukrainian instead of the original German. In Keri-Lynn’s version of the Ninth, Schiller’s “Ode to Joy” becomes the “Ode to Glory,” which is “Slava” in Ukrainian, the rallying cry for their victory.

In the film we made about Rostropovich, he explained that he was given lasting advice by his mentor and friend, Shostakovich, who himself was a victim of Stalin’s artistic oppression. Shostakovich told Rostropovich that in the fight for artistic freedom to think of himself as a soldier of music. My wife and the members of the Ukrainian Freedom Orchestra are today’s soldiers of music. And that’s the credo I aspire to, as well.

What was your vision for creating The Met: Live in HD, and how has this initiative evolved?

This has been the most important media initiative of my tenure at the Met. But in fact, our history of harnessing technology to share performances goes back nearly 100 years.

In 1931, while the United States was still in the throes of the Depression, the Met was making use of electronic media with its radio broadcasts to help in its fight for financial solvency and a wider public. Today, not much has changed. We’re fighting harder than ever for post-pandemic financial solvency and a wider public, but we have new tools at our disposal, from social media platforms to the continuing success of The Met: Live in HD, our series of live performance transmissions into movie theaters and performing-arts centers around the world.

The cinema audience is coming back more slowly than at the opera house, but we’re still uniting hundreds of thousands of opera fans for nine times this season as we transmit our 1 PM matinee performances live into movie theaters and performing arts centers from as far south as the southernmost reaches of Argentina and Uruguay to as far north as the Arctic Circle where audiences in Tromso, Norway, faithfully gather. We’re seen live from the West Coast to as far east as Jerusalem and on a time-delayed basis in Asia, Australia, and New Zealand, where the time difference is too great. Our transmissions are being seen on every continent except Antarctica. To serve our global audience, we utilize six different satellites that carry signals encoded with subtitles in eight different languages.

More than 30 million people have seen the Met in movie theaters so far. Who would have thought that so many would be enjoying grand opera and a hot dog for less than it costs to attend a baseball game?

How has resilience played a role in your career?

One of our board members was fond of quoting an aphorism he attributed to Churchill – that the only endeavor more complicated than grand opera is war. It turns out that Churchill never said that, and I’ve never been to war, but having led the Met for all these years I can imagine what it feels like to be a battle-worn veteran – although I don’t think I’m suffering from post-operatic stress syndrome just yet.

But in terms of aging and wear and tear, I think it would be fair for every year as head of the Met to be calculated in dog years, since dealing with the various forces and factions – we have 15 unions – at the world’s largest performing arts company is a formidable task.

With a budget of over $300 million and earned revenues that only cover a portion of our expenses, the Met’s challenges are Herculean. Since the pandemic, they’re even greater, which is why the Met has been moving forward with an accelerated artistic agenda that is intended to draw new audiences and new donors.

During the COVID pandemic, you launched Nightly Met Opera Streams with complete performances from the company’s voluminous archive streamed online. How did this effort exemplify the meaning of “The Show Must Go On?”

During the first months of the pandemic when most people were holed up in their homes, we provided them with artistic solace through our nightly streams of opera. It strengthened our bond with the public both near and far, and actually won new fans for opera who suddenly had a lot of time on their hands to explore our art form.

With all that you have achieved and the many awards that you have earned, are you able to take moments to reflect on your accomplishments?

I’m too busy to reflect on past accomplishments (other than for this article). It is the responsibility of the Met to win new audiences for opera, since no matter how venerable our 138-year-old opera company is, there is no free pass into the remainder of the 21st century. That’s why we are not only commissioning new operas, but also studying new models for our performance schedule; why we introduced Sunday matinees a few seasons ago; and why we’re developing more programs in which to bring opera into the community.

It’s why we’re planning to increase our educational efforts in New York and across the nation, and why we’re adding new digital platforms for our performance contents. And it’s why we chose one of the world’s most brilliant conductors, Yannick Nezet Seguin, to become the Met’s Music Director. Yannick is now in the midst of his fifth season, and has been winning new fans for opera and the Met. A few weeks ago, Yannick and the Met won our fourth Grammy in a row for best opera recording of the year for Terence Blanchard’s Champion. The previous consecutive Met winners were Terence’s Fire Shut Up in My Bones, Philip Glass’ Akhnaten, and the Gershwins’ Porgy and Bess.

With several more years to go in my current contract, I’m already one of the longest serving managers in the Met’s history. Yet, I realize that my work is not yet done. It won’t be completed until the Met is on firmer financial footing and our artistic path forward is certain. Since the Met is the world’s leading opera company, the future of opera relies on the Met to succeed – and we’re dedicated to achieving that goal.![]()