![]()

ONLINE

![]()

ONLINE

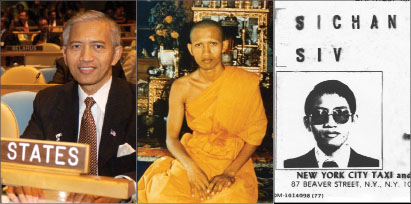

No ordinary journey: Ambassador Sichan Siv has traveled around the world, and gone from Buddhist monk (above right), to taxi driver (center), to UN Ambassador (left).

Golden Bones

EDITORS’ NOTE

Sichan Siv, the former U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations (UN), is the only official in the U.S. government who was born in Cambodia and has held a high-ranking position at the White House, in the office of the U.S. President.

For our readers who may not have a full appreciation of what life was like in Cambodia in the mid-’70’s, could you share with them, by way of example, the experiences and tragedies you and your family suffered?

In 1970 Prince Sihanouk was deposed by Lon Nol, ending a peaceful period. The Vietcong/North Vietnamese army [VC/NVA] broke out of their sanctuaries in eastern Cambodia and attacked Cambodian forces everywhere. A 1973 agreement in Paris ended the Vietnam War, but the Khmer Rouge [KR] took over the fighting from VC/NVA. In 1975, the unexpectedly victorious KR turned Cambodia into a land of blood and tears. Nearly two million people died of exhaustion, starvation, and summary execution. Of my 16 family members who left Phnompenh together on April 17, 1975, I am the only survivor. My mother, older sister, brother, and their families were clubbed to death by the KR. In February 1976, I escaped to Thailand and was jailed for illegal entry. I spent a few months teaching English to fellow refugees and was ordained a Buddhist monk. On June 4, one month before America’s bicentennial, I arrived in Connecticut with $2 in my pocket.

Why did you choose the title Golden Bones for your book?

Cambodians call someone who is very blessed or lucky a “person with golden bones.” The book cover pictures me praying by myself in front of a Buddha statue at Angkor Wat. It was during my first return to Cambodia in March 1992 that I visited my father’s village in Takeo. The villagers knew that I had survived the KR massacres, had gone to America, and was working for the President of the United States. They called me the “man with golden bones.”

Siv recounts the story in his book Golden Bones, to be published by HarperCollins in summer of 2008

For people who read about your life and/or hear you speak, the word “inspiration” naturally comes to mind. You, in turn, encourage people to “never give up hope,” a plea your mother instilled in you. Could you elaborate?

Hope kept me alive for a year under the Khmer Rouge. I never knew if I would be alive the following day. When I woke up, I said to myself I would make it to freedom. Upon arrival in America, I tried to forget a painful past and to adapt myself to a new environment. I learned from other people, and I did everything the best way I could. It was my mother’s wisdom that helped me move onward and upward.

What advice would you offer young people?

Hope should always be with us, even on our brightest days. Whether you are an entrepreneur, a farmer, a teacher, in the military, in government, or in the private sector, you need to have hope for a better tomorrow. This word also has a strong impact on young people. From Newberry College in South Carolina to Troy University in Alabama to UCLA, students will remember my message of adaptation and altruism. They had dreams in the classroom. They have hopes at graduation. They can turn these into reality. Robert Goddard put it best: “It is difficult to say what is impossible, for the dream of yesterday is the hope of today and the reality of tomorrow.”

How do you define leadership?

Leaders have courage, integrity, and vision. They see a larger landscape, not just forests, mountains, and rivers, but a 360 degree view; further away, not just next month, but years into the future. Leaders assemble good teams to work effectively together. They motivate them, care for them, and provide examples for them to follow. Leaders see challenges as opportunities and make difficult decisions based not on gaining popularity, but on the greater good. For me, leadership is the ability to instill hope and optimism.

With your global travels, you manage to visit Cambodia regularly and are optimistic about the country’s future economic development prospects. What makes you so?

Cambodia is an ancient culture and civilization. After decades of turmoil and upheaval, it has held an election every five years since 1993. It has come a long way in a decade and a half to become a “flawed democracy.” There is still a lot of corruption and impunity, and the rule of law must be strengthened. Compared to many post-conflict societies, Cambodia is faring well. The future is looking brighter as the country becomes more politically mature.