- Home

- Media Kit

- Current Issue

- Past Issues

- Ad Specs-Submission

- Ad Print Settings

- Reprints (PDF)

- Photo Specifications (PDF)

- Contact Us

![]()

ONLINE

Venture Philanthropy:

Taking Risks,

Betting on People

Editors’ Note

Wendy Schmidt is a philanthropist and investor who has spent more than a dozen years creating innovative non-profit organizations to solve pressing global environmental and human rights issues. Recognizing the human dependence on sustaining and protecting the planet and its people, she has built organizations that work to educate and advance an understanding of the critical interconnectivity between the land and the sea. Through a combination of grants and investments, her philanthropic work supports research and science, community organizations, promising leaders, and the development of innovative technologies.

As president of The Schmidt Family Foundation, a non-profit she started in 2006 with her husband, Eric, she leads the team that works to address the global crisis of climate change through grants and impact investments in renewable energy, sustainable agriculture, human rights and marine technology. The grant-making arm of the Foundation, The 11th Hour Project, focuses on supporting local organizations and solutions that protect human rights and build resilient food and energy systems. In 2015, she started Schmidt Marine Technology Partners, another program of The Schmidt Family Foundation, that supports the development of promising technologies that solve complex ocean health issues and have strong commercialization potential.

Wendy and Eric also co-founded the Schmidt Ocean Institute in 2009 to advance oceanographic research through the development of innovative technologies, open sharing of information and broad communication about ocean health. The institute operates Falkor – the only year-round, seagoing philanthropic research vessel in the world – and a 4500m remotely operated underwater robotic vehicle, SuBastian. Both are made available to the international science community at no cost. Schmidt has extended her oceans-focused work to the sporting world through 11th Hour Racing. She co-founded the organization in 2010 to work with the sailing community and maritime industry to advance solutions and practices that protect and restore the health of the oceans.

In 2017, Wendy and Eric founded Schmidt Futures, a philanthropic initiative that finds exceptional people and helps them do more for others together. In the Fall of 2019, the Schmidts announced a $1 billion philanthropic commitment to identify and support talent across disciplines and around the world to serve others and work to solve the world’s most pressing problems.

Organization Brief

Established in 2006 by Wendy and Eric Schmidt, The Schmidt Family Foundation (tsffoundation.org) works to advance the wiser use of energy and natural resources and to support efforts worldwide that empower communities to build resilient systems for food, water, and human resources. Through a combination of grants and investments, the Foundation promotes an intelligent relationship between human activity and the planet’s natural resources.

When you and your husband, Eric, started The Schmidt Family Foundation in 2006, was this something that you always knew you had a passion for and what was your vision for the Foundation?

When Eric and I got married as graduate students in 1980, we never saw what was ahead of us, much less that we would have the opportunity to shape some significant philanthropic work.

In 2004, when Google went public, I had been running an interior design business for 16 years, following several years working in high-tech communications. I’d joined the board of the National Resources Defense Council and was on a steep learning curve about environmental issues. With sudden wealth came an enormous sense of responsibility to do something meaningful, and as Eric was occupied as CEO and later chairman at Google, the task to embark on our philanthropic journey fell to me.

The following year in 2005, Vice President Al Gore was traveling around the country giving a slide show presentation about “global warming,” and my colleague, Amy Rao, heard the talk at UC Berkeley early that summer. In September, we met for lunch in Palo Alto and began discussing how to bring this talk to Silicon Valley – a place of innovation, where people look for answers and are motivated to solve problems. As we considered how to get the minds of Silicon Valley working on the issues around climate, little did we know how critical those early conversations would become.

Working with Stanford University, we organized a presentation of Al Gore’s talk in early December at Memorial Auditorium, filled to capacity with 2,000 people, along with a discreet film crew, who were busy filming An Inconvenient Truth. Immediately following the screening, we hosted a dinner for 350 people that included notable Silicon Valley entrepreneurs and engineers, along with local political and business leaders, scientists, and representatives from environmental groups, to have a conversation together about the global challenge Gore had identified. What’s our response, Silicon Valley?

Our Foundation began with this focus on educating important audiences about human-induced climate change but within the first year or two, it was pretty clear to us that addressing climate change means addressing the things that are directly contributing to it. That means looking at the system that has led to this predicament, as a whole, and finding points of intervention.

Our energy program has focused on advancing renewable energy and increasing access to it for everyone. We can’t really move away from fossil fuels without including everyone. Beyond transitioning the world’s energy systems, we can’t beat climate change if we don’t look at the world’s food system. We have to look at the way we grow and distribute food and its impact on our soil, our air, our health, on the health of animals, even on the health of the ocean. And then, finally, human rights are deeply woven into these problems when you start to look at them holistically.

This is the center of The Schmidt Family Foundation’s work. We’re focused on identifying and reversing the dangerous systemic changes to the world’s land and ocean from human industrial activity that have happened in just the last 100 years or so. We think we can help move the dial towards better outcomes.

Eric and Wendy Schmidt view a livestream of an underwater

robotic vehicle, SuBastian, in the control room of Falkor,

their research vessel that is made available

to the international

science community at no cost. Falkor is the

research platform

for Schmidt Ocean Institute, a nonprofit organization that

advances innovative ocean science.

Is your support of projects such as the 11th Hour Project, the Schmidt Ocean Institute and Schmidt Marine Technology Partners interrelated?

Absolutely. Our programs tie together and work together. The different entities focus deeply on different aspects of the general issue I’ve described. You can think of the entities that we have created, including Schmidt Futures, as a distributed network. We’ve grown up in Silicon Valley and watched how technology has changed the way we do everything over the past 40 years. The computer that sent men to the moon when I was a child was probably the size of the building that you’re sitting in and, today, you have that much computing power in your cell phone.

The transformation has been enormous, and so much of it has depended on the development of powerful networked systems. We think of our individual projects working together synergistically, sharing information, relationships, and tools across the network. We find this is a stronger way to operate and to pursue our mission than to operate as a single enormous entity with all sorts of departments in it.

You created Schmidt Futures in 2017. What was your vision for this initiative?

Schmidt Futures is a big bet on people and the development of talent in the world. We call Schmidt Futures a facility for public benefit, rather than a conventional charity, and it’s trying to do things in new and creative ways that are rarely done in philanthropy. There is a lot of investment, obviously, in science and research, but Schmidt Futures also focuses on people and talent and being able to give people the tools they need to be successful with an eye toward public service.

We have a couple of programs that have just gotten started. The Rise program is focused on 15- to 17-year-olds around the world. Imagine giving people of that age who are recognized as talent within their own communities the tools to advance their gifts in the world with an eye towards sharing them for public service and creating a generation of people and successive generations of people who share those values. We think that this could make a huge contribution to global leadership.

The Schmidt Science Fellows program is in its third year now. This is a fellowship for post-doc students to help them look outside the discipline they studied and pair them with a different discipline so they can bring their insights into new areas of science to try to open up the paths of research. This goal is true for so much of what we do in science, from the ocean science at Schmidt Marine Technology Partners and the Schmidt Ocean Institute to the work of the Schmidt Science Fellows. Think of it, again, as building a powerful network of skilled people across disciplines.

The exciting thing about our work to support science is that the more you discover, the more you realize how much you don’t know. That signals to us that we could be on the threshold of a whole new age of scientific discovery if we’re willing to create those opportunities.

What is your approach to philanthropy and while many look at it from a dollar standpoint, for you is it about more than providing money?

Absolutely, yes. For us, I say philanthropy is really just velocity – it’s putting energy into something that wouldn’t happen otherwise. It sends a signal. Philanthropic investment in outcomes has a unique risk perspective, unlike business and government, which tend to follow the investment trail once it’s established. We’re out in front, and we really should be the risk-takers: that’s our job. We try to open doors so others can come through. We focus on the individuals in an organization, since any organization is only as good as the people in it. Much of what we’re doing is very hands on, it’s very grassroots, and we’re very personally involved.

We have an impact investment group that’s perhaps among the most exciting things we do because you can see the results of these investments within a fairly short period of time. Most of the problems we address as philanthropists are very long-term, and we’re unlikely to see resolutions in our lifetime. Still, we’re trying to move the dial and shift behavior, or beliefs, or the way problems are thought about and dealt with. This is a lifelong enterprise and you’ll never get much feedback. I tell people it’s going to be 10 years before you know whether you’ve had any impact at all, so this work requires a great deal of patience and focus.

On the investment side, we’ve supported proposals that have elevated the market presence of otherwise subsistence farmers growing rice, coffee and cocoa. Other organizations have worked in new ways to combat illegal fishing and plastic pollution and to safeguard sustainable fisheries as they find new markets around the world. Others have found new ways to advance habitat health and developed new tools for ocean research. One of the successful technologies recently developed is Saildrone, with its autonomous wind- and solar-powered ocean drones that have a slew of commercial and science applications and can monitor climate and sea conditions in real-time. When you see things like that come into fruition after a cycle of investments and then be opened up to the broader investment community, you feel like you’ve really led something important. That’s a great role philanthropy can play.

I recommend that the business community find out where the impact investors are putting their money because those could be the big moves for them as well.

How critical is a strong public/private partnership in order to effectively address the major challenges facing the world?

It’s very important that there be strong public/private partnership. I’ve been a partner with the Ellen MacArthur Foundation in Great Britain for a number of years and we’ve been working to support the development of a new, circular industrial economy – replacing a wasteful linear economy where materials are manufactured and thrown away – focusing on reimagining replacements for plastic packaging. Corporate partners are important here because we aren’t the people in labs who can create packaging that won’t end up in our waterways and ocean environments, although we can and do seed the innovation cycle, as well as the phases of early investment. But to scale these solutions, you need partners, even those who may have been involved in causing some of the problems, focusing on the solutions.

You need everybody involved, including government and regulatory bodies. The policy side of this is enormously important, but governments don’t tend to be risk-takers. Governments tend to follow instead of lead, so we can’t wait for government to lead.

If you can make a good future case for business about these market transformations, businesses naturally get interested, and there’s a growing recognition that waste is expensive in a resource-constrained world. You can’t really have a solution that doesn’t have a good economic basis, so we have to think of it very much that way.

I have a rule I work by, which is that it doesn’t take everybody to have a revolution. People have studied this question in many different ways. It turns out that, in any kind of change you want to make in any society, it takes 10 percent of the population to be deeply committed, and they will then change everybody else. What Eric and I are working toward is to get that 10 percent convinced and moving together in a direction of positive change. That turns out to be the secret if you do it right.

Do the skills that made you and Eric successful in the business world translate into doing effective philanthropy or was there a learning curve when you started this work?

There is always a learning curve. I’ve been working in philanthropy since 2006. Eric is a little newer to it but it’s now becoming more of a full-time focus for him as well. There are always things that you can bring from whatever you’ve done in business, but philanthropy is the kind of work that doesn’t give you an answer about what you’re doing for a very long time. All you can do is go out and be innovative and try things. The things that pertain to Eric’s work in technology involve iterating, trying, inventing, failing fast, learning from your mistakes, persistence and flexibility and all those play a huge role in the way we approach philanthropic work. It’s a natural language for us.

Eric is an engineer and a technologist; I’m an intuitive and artistic person, and all perspectives have a place in this work. You really need, at the bottom of it all, a commitment and a recognition that you have a responsibility and you can share that mission with others. It’s great to have that drive on your own, but you’re really propelled forward when you’re surrounded by people who believe in it too. It’s very important to build strong organizations with deeply committed people who share a vision and approach.

Is it important to remain focused on the key areas where you feel that you can make the most impact and is it sometimes hard to say no to certain causes when there is so much need in the world today?

That’s the challenge when you are trying to use wealth to solve problems. It can be absolutely overwhelming and why it’s quite helpful to understand the lens through which you’re looking at your work. You can’t solve all the problems in the world. You won’t cover every philanthropic opportunity, you simply can’t. You need to understand where your focus is and the scope of the network you can build. It’s remarkable to me that over the past 10 years, the network of people that we’ve built are working on things slightly different from each other, but they’re all related. There’s a great deal of crossover; you can feel that synergy and you feel you’re all moving in a particular direction.

For example, our 11th Hour Project team working on regenerative agriculture practices is connected with our 11th Hour Racing team that uses the sport of sailing to educate people about the health of our ocean. These two organizations work together, connecting what happens on land with what happens in the ocean. A current focus is on a pilot project in Rhode Island demonstrating how composting is a land-based activity that supports ocean health.

We’ve combined a lot of disciplines and interests where people might not have talked to each other before. I grew up in a world where a lot of information was in silos, certainly in academic circles. Today, the opportunity is to cross-pollinate. If everything is indeed interconnected, then we all need to be talking to each other across all disciplines. We all face the same essential issues as humans. We have to examine where humans fit into this network of living systems and make it work for the planet as a whole.

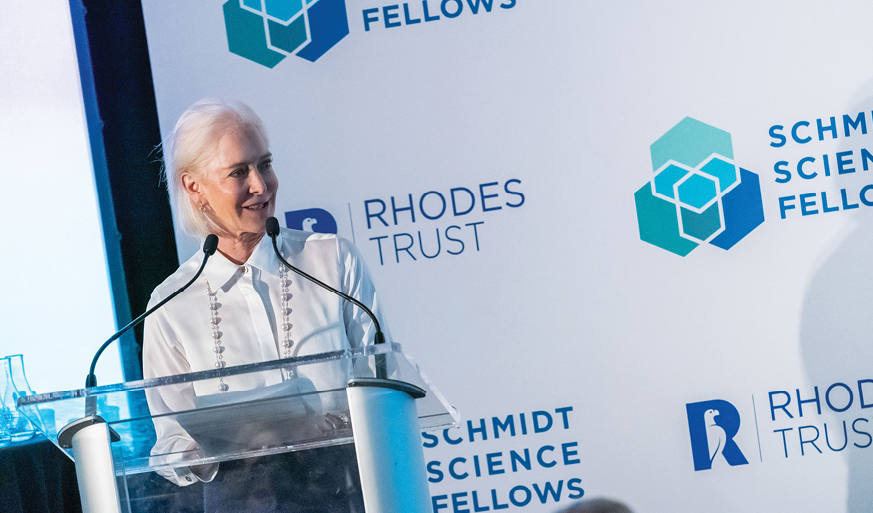

Wendy Schmidt addresses the 2019 class of Schmidt Science

Fellows, a program of Schmidt Futures in partnership

with the Rhodes Trust. The year-long postdoctoral research

fellowship follows the participants’ completion of their Ph.D.

in the natural sciences, computing, engineering or mathematics

and places them with global scientific leaders and internationally

renowned labs in a scientific discipline different than their

core area of study.

How hard is it to be patient when you are dealing with such large, complex issues?

We have to look at what we’re doing against the scope of human history, so we’re talking about the blink of an eye. Patience is essential to the work because you would feel like you weren’t getting anywhere if you weren’t patient. Eric and I have a saying we share which is, “You need three things: you need patience, you need information and you need alternatives.” If you think about what you’re doing with those options in front of you all the time, you can sometimes just breathe, neutrally buoyant, and then move forward when the opportunity arises. You should understand what the long-term goal is and be very flexible about how you’re going to get there.

We’re always learning, and the paradigms we might have set for ourselves a decade ago may need to be revisited. What is the right move right now? What are the tools right now? I always say that many times in philanthropy, when you give the investment and make that commitment is often as important as how big it is.

I recently received a letter from one of our grantees, Paul Farmer at Partners in Health, in Haiti. He wrote to us on the tenth anniversary of the horrible earthquake that devastated that country and killed 300,000 people. He wrote from University Hospital in Mirebalais, which is now the world’s largest solar-powered hospital providing healthcare to more than 1 million patients each year. Back in 2011, The 11th Hour Project responded within days to Paul’s distress post-earthquake, providing desperately needed funding to install the hospital’s solar panels so it could remain functional in a country where the infrastructure had been destroyed. Good things happened because we could make a decision quickly, knowing who was asking and why. Timing and relationships matter.

Wendy Schmidt tours a village in the Virunga National Park

in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, where her

family foundation has supported park officials in protecting

one of the world’s largest national parks and communities

living in and around the park from illegal

fossil fuel extraction.

Another good example is in the Democratic Republic of Congo and the Virunga National Park. Virunga was the subject of an Academy Award-nominated documentary that told the story of one of Africa’s largest national parks and the struggle to keep an oil and gas company from exploring for oil inside the park where the mountain gorillas are under threat from poachers. We got involved with Virunga not only to protect this unique ecosystem, but also to look at the park as a useful economic opportunity for that country. Working with Emmanuel de Merode, the park’s storied director, we considered how an iconic park in a war-torn country could create an economy that didn’t involve poaching and didn’t involve depleting the resources of the area.

We helped to fund the development of two micro hydro-powered dams in the park that over the past six years have delivered clean, renewable energy to a million people in villages around the park. People, primarily women, who previously had to spend their daylight hours searching for firewood now have electricity from a clean, renewable resource. Electricity means streetlights that increase security. It means people have power for cooking and reading at night. It means hairdressers, restaurants and other small businesses, and even a soap factory. A new economy evolves when people have access to power which is why we believe that access to clean renewable energy is a human right in the 21st century. Without it, you’re not even on the same playing field.

Electric power, along with a series of micro loans to businesses in these areas, has generated all kinds of alternative job opportunities, where young men don’t feel their only choice is to join a local militia. The DRC is still a turbulent country with many threats but if, through philanthropy, it’s possible to create economic opportunity for people and they know that there’s somebody who’s got their back, they have a chance.

When you’re dealing with these long-term issues, how important is it to take moments to celebrate the wins and to appreciate what the Foundation has been able to accomplish?

Little victories add up over time and every win counts, but to be honest, we don’t spend much time celebrating. Each year, we bring together a large group of The 11th Hour Project’s grantees from each of our programs to a two-day gathering in San Francisco. It’s a chance to share examples of the work and give people an opportunity to meet and talk to one another. Sometimes they find ways to work together across the programs. It’s great for people to hear what others are doing, what their successes and challenges are. Our team comes back every year feeling a little bit surprised and humbled by the impact of what we are doing every day.

You can never really see the whole picture, but when you get people together and you see year over year what did make a difference, it encourages you and focuses our programs on what’s working. It’s an opportunity for the cross-pollination we deeply believe in to happen. All in all, we find problems are often more the same than they are different. ![]()