- Home

- Media Kit

- MediaJet

- Current Issue

- Past Issues

- Ad Specs-Submission

- Ad Print Settings

- Reprints (PDF)

- Photo Specifications (PDF)

- Contact Us

![]()

ONLINE

![]()

ONLINE

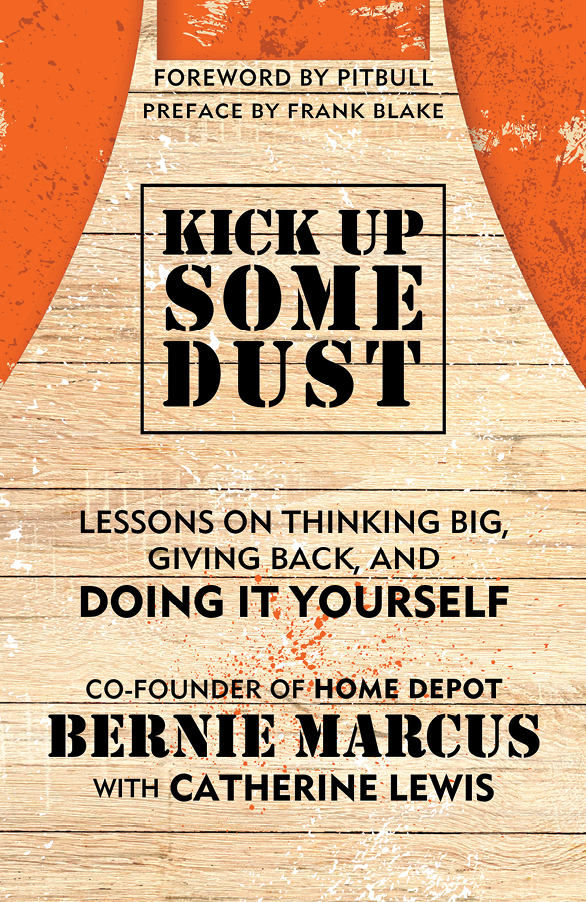

Kick Up Some Dust

Editors’ Note

Bernie Marcus cofounded Home Depot, the world’s largest home improvement retailer, and served as its inaugural CEO and as its chairman until his retirement in 2002. Over the last several decades, he has redirected his entrepreneurial spirit toward hundreds of charitable endeavors to solve big problems. He has given away more than $2 billion and is a signatory of the Giving Pledge. He is the author of KICK UP SOME DUST: Lessons on Thinking Big, Giving Back, and Doing It Yourself.

What interested you in writing the book, Kick Up Some Dust, and what are the key messages you wanted to convey in the book?

I wrote the book because I want to remind readers that the American Dream is still alive and kicking. I was born to immigrant parents and lived in a walkup tenement. We never had much money, but my parents worked hard to make it possible for their children to succeed. The big part of my story doesn’t start until I was fired from Handy Dan when I was 49. Most of my friends were retiring, and I was just thinking about starting Home Depot. I had a lot of experience in business, made plenty of mistakes, but put it all together with great partners in Arthur Blank and Ken Langone. The book is also about what I did after I retired. I knew I needed to use the same lessons we learned building the business to help solve big problems. I always believed in the Jewish concept of tzedakah – giving back. You can’t be selfish. If you become successful, you have to find a way to help others. I was lucky that the “do it yourself” lessons learned from Home Depot helped transform my approach to philanthropy. The key lesson in the book is that you can’t expect others to do the work for you – either in business or giving. I learned this lesson when I began my work with organizations that supported families with autistic children. I knew nothing about the condition, but had an employee whose son was suffering. So, I got involved, asked questions, made calls, and helped build the Marcus Autism Center and fund Autism Speaks. This took years, and I refused to just write a check and walk away. I had an obligation to make it successful.

Who is the book targeted to and who are you hoping to reach with your story?

The other day, I had a conversation with a very successful financier who retired at age 55. I had to ask, “What do you do all day?” He listed his schedule – get up, eat a bagel, read the paper, take a walk, eat lunch, go shopping with his wife, maybe play some golf, then spend time thinking about how to fill tomorrow. I can’t imagine being that disengaged. So, I hope this book speaks to people who have been successful and are looking for meaningful ways to give back. But it should also appeal to entrepreneurs and young people who are creative and willing to take risks and are just beginning their careers. I hope to show hopeful entrepreneurs that if you have the incentive, courage, and intuitiveness you can develop what you want in this world. A lot of people don’t know where to start and reading about my story – warts and all – might give them some inspiration. The book will also resonate with people who may not have a lot of resources, but have time and energy to help in their community. I remember when I was starting out, I didn’t have much, but got involved with City of Hope in Los Angeles. My volunteer work there changed my whole perspective on philanthropy. I also think the book will be popular with Home Depot associates, past and present, and customers. There are a lot of behind-the-scenes stories that shed light on how we built the business that may surprise readers.

“The key lesson in the book is that you can’t expect others to do the work for you – either in business or giving.”

You faced many challenges during your career. How critical was resilience to your success and what were the keys to continuing to stay optimistic and push forward?

I learned early on from my mother that bad things happen, and you have to compartmentalize them and keep moving. Don’t “Monday morning quarterback” your life. I once had a retail analyst ask me if I ever made any mistakes. I had to laugh and say, “Are you kidding me? Too many to even mention, but I try to learn from them and focus on how to use that information to do better next time.” In baseball, a good hitter might average .300. I would say, I’m in the .280 range. The whole point is not to think about what you did wrong, but what you did right. I believe you have to go forward and can’t look backward. People who look backward don’t succeed in life. I worry about people who constantly second-guess their decisions. The key is to take a risk, make the mistake, figure out what happened, fix the problem, and never do it again. That’s the only lesson to be gained from looking back. I’m 93, and I’m planning out my next five years. Writing this book was a bit of a challenge because I had to think about the past, and there are some painful memories that I had to relive. But they don’t define me. If I had looked back on those memories every day, I wouldn’t have been able to move forward.

What do you see as the keys to effective leadership and how do you describe your management style?

There are two key elements to effective leadership. The ability to listen is the main one. A lot of successful people – CEO’s and politicians – lose the ability to communicate effectively because they don’t slow down and listen. If your mouth is open, your ears are closed. The second key is to surround yourself with people who are smarter than you. You can’t surround yourself with people who only say “yes” – it doesn’t work in business. I know my strengths, and always tried to hire people whose traits complemented my own and brought new perspectives. That was the secret to success at Home Depot. We empowered our associates to speak up – if something wasn’t working, tell us. This gave us helpful feedback – sometimes from a longtime manager, or a disgruntled customer, or a 16-year-old kid who had been working for two weeks with an idea that saved us millions of dollars. Other employees would hear how those ideas came about and bring new ideas to the table – and then that just became part of the culture. Reward people for sharing their opinions and you just might learn something.

Do you feel that leadership can be taught or is it a skill that a person is born with?

Some people are born leaders. They just have that gene, but I do believe that plenty of people can excel when given the opportunity, and they just might surprise you. Great leaders often come from unexpected places. Frank Blake was a lawyer who worked for the EPA, Vice President George H. W. Bush, and General Electric, before coming to Home Depot. He worked in corporate business development, so would not have been the most logical choice for the CEO role, but he was terrific. Then he helped pick his successor Craig Menear, who worked in merchandising at Home Depot, and he was equally good. The thing that impresses me is how many women have taken on leadership roles in business. Ann-Marie Campbell, who came from Jamaica, started as a cashier and is now executive vice president for U.S. stores and international operations at Home Depot. I learned long ago that leaders are often great employees who just need to be given an opportunity. They don’t need a Harvard MBA or even a college degree. Give people a chance to show what hard work can do for them and their employer. That was one of our values at Home Depot.

What has made philanthropy so important to you and how do you decide where to focus your philanthropic efforts?

I worked in business for more than 70 years, and I don’t feel the need to make any more money. But I’m not done yet. In 2002, soon after I retired from Home Depot, I was able to commit myself to giving full time. The Marcus Foundation had been up and running since 1989 and, at first, we used a “buckshot approach.” We donated money here and there, and I felt like we helped fix some small problems, but we were not making a measurable difference. What could we do differently? We hired a consultant and narrowed our focus to five areas: Jewish causes, medicine, youth, free enterprise, and community, especially veterans. Our goal is to support causes that have significant impact – like our work with the Avalon Network to help veterans with TBI and PTSD, or developing a liquid biopsy to detect early-stage cancer at Johns Hopkins. I have friends who fly all over the world and sail on yachts. That doesn’t interest me. My new bottom line is helping people overcome issues in their lives. People come up to me and say I changed their life. What is that worth? Far more than any amount of money. Philanthropy that makes a difference is what gives me satisfaction.

Do the same skills that made you successful in business translate to being effective in philanthropy?

Yes, that was the whole impetus for writing the book. I asked myself, how can you take the lessons in business and translate that into helping others? I believe in entrepreneurial philanthropy, and try to persuade others who have been successful to join me – whether they are in their 20s or 80s. I gave a speech about giving in Montreal and got a letter from a guy in the audience a few months later. He said he went home to Florida and was so moved that he dedicated himself to building a children’s hospital. He didn’t just write a check – he got involved – and said he is now the happiest person in the world. That’s what I call success.

You have achieved so much in your business career and through your philanthropic work. Do you enjoy the process and take moments to appreciate what you have accomplished?

Every day, I wake up and think: “What are we going to try today?” And when something is promising, then I pour energy into finding out how to scale it to serve a national and international audience. That’s what The Marcus Foundation has done with our giving to veterans. Start small, think big, and expect a lot of failure. Not everything we try works, and we won’t scale it until we’re sure it is successful. I’ve also learned not to fall in love with my own bullshit. You have to be careful and not get caught up in the hype. Make sure the program or treatment really works – test and test again. We’ve funded clinical trials that I would bet my life on that did not pan out. There’s a lot of disappointment, but if three out of ten things work, that’s a success. I do enjoy hearing the stories from the parents with a child who gets life-saving treatment, people who survived a stroke, or veterans who are healing from traumatic brain injuries – that is an incentive for me. That’s what keeps me going.

What advice do you offer to young people beginning their careers during this unprecedented time?

My best advice is to be grateful that you were born in this country. There is no place on earth that prizes innovation like America. Our free-market system encourages you to be creative, work hard, and succeed. That’s what we did at Home Depot and do every day with our philanthropy at The Marcus Foundation. If I was starting out today, I would hope that somebody like my mother would tell me I could do anything, be anything. Work hard, own your mistakes, don’t let failure defeat you, and keep a positive attitude. And remember, you are never too young or old to do something big. I just wish I had another lifetime to see you do it.![]()