- Home

- Media Kit

- MediaJet

- Current Issue

- Past Issues

- Ad Specs-Submission

- Ad Print Settings

- Reprints (PDF)

- Photo Specifications (PDF)

- Contact Us

- PRIVACY POLICY

- TERMS OF USE

![]()

ONLINE

![]()

ONLINE

Sebastian Junger

A Conversation with

Sebastian Junger

Editors’ Note

Sebastian Junger is the #1 New York Times Bestselling author of The Perfect Storm, Fire, A Death In Belmont, War, Tribe, and Freedom. As an award-winning journalist, a contributing editor to Vanity Fair, and a special correspondent at ABC News, he has covered major international news stories around the world and has received both a National Magazine Award and a Peabody Award. Junger is also a documentary filmmaker whose debut film, Restrepo, a feature-length documentary co-directed with Tim Hetherington, was nominated for an Academy Award and won the Grand Jury Prize at Sundance. Restrepo, which chronicled the deployment of a platoon of U.S. soldiers in Afghanistan’s Korengal Valley, is widely considered to have broken new ground in war reporting. Junger has since produced and directed three additional documentaries about war and its aftermath. Which Way Is The Front Line From Here?, which premiered on HBO, chronicles the life and career of his friend and colleague, photojournalist Tim Hetherington, who was killed while covering the civil war in Libya in 2011. Korengal returns to the subject of combat and tries to answer the eternal question of why young men miss war. The Last Patrol, which also premiered on HBO, examines the complexities of returning from war by following Junger and three friends – all of whom had experienced combat, either as soldiers or reporters – as they travel up the East Coast railroad lines on foot as “high-speed vagrants.” Junger is the founder and director of Vets Town Hall. He has also written for magazines including Harper’s, The New York Times Magazine, National Geographic Adventure, Outside, and Men’s Journal. His reporting on Afghanistan in 2000, profiling Northern Alliance leader Ahmed Shah Massoud, who was assassinated just days before 9/11, became the subject of the National Geographic documentary Into the Forbidden Zone, and introduced America to the Afghan resistance fighting the Taliban.

Will you highlight your journey to becoming a journalist?

I went to a liberal arts college and majored in anthropology since it interested me. I had no sense of practicality at the time or thought about what I would do after college, and before I graduated I ended up doing field work on the Navajo Reservation. During college I had been a pretty good long-distance runner, so I wrote a thesis on Navajo long-distance running which is a very old tradition in that culture. The thesis was about that tradition and its modern expression. I realized how much I enjoyed doing the research and studying the subject and writing about it. I figured this was pretty close to what journalism must be like, so I thought that maybe I would become a journalist.

There were also a number of great short story writers during that time – Tobias Wolff, Grace Paley, Ray Carver – who I was enamored with, not thinking about how utterly impractical that was in trying to make a living. I was intrigued by the art form, and I began waiting tables, writing short stories and articles, hitchhiked around the country, traveled to Europe where my dad was from, and had a lot of experiences, but nothing that was geared towards a career. I had gotten a few things published, but it was not really going anywhere. In my late 20s, I was sitting next to a guy in a bar who owned a tree company, and he told me that he needed a climber and asked if I was willing to work a few days a week. I thought it sounded good and agreed to be a climber who goes up 80 feet in the air with a rope and a chainsaw to cut down trees. It is quite acrobatic work, and dangerous if you make a mistake. I realized that there was no random danger – it is all physics and if you get killed, it is because you screwed up. I enjoyed the concept that there were risks, but the risks were controllable. One day I did screw up and cut the back of my leg with a chainsaw, and while I was recovering I was thinking about writing a book about dangerous jobs.

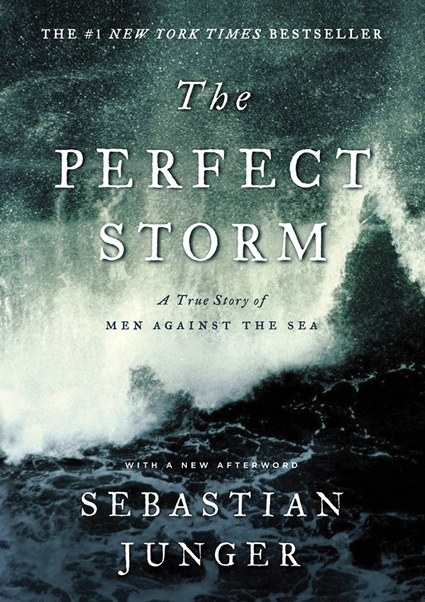

At this time, I was living in the town of Gloucester and a huge storm hit the coast of New England. A local boat named the Andrea Gail was lost in the storm, and while I did not know any of the crew, I thought about writing a book to tell the story of the Andrea Gail since this happened in my community. That became my first book, The Perfect Storm. I researched that story for many years, and during this same time there was a civil war occurring in Bosnia, so I took a duel approach to my failed future and decided to write a book proposal for The Perfect Storm and go overseas to be a war reporter. I actually had an agent at the time who saw some promise in me and took a chance on me. I sent the book proposal for The Perfect Storm to him, went off to Bosnia to cover the war, and completely fell in love with the work of war reporting. I was with a few other freelancers and we traveled all across Bosnia. The war was in a stalemate so there was not a lot of combat, but I was able to experience this society that was in crisis and stagnating. There were businessmen in suits who were boiling coffee in a pot on a twig fire in the courtyard of their apartment buildings. It was an eye-opening experience. I had to come home because my agent had sold The Perfect Storm, and even though it was not much money, I was thrilled. This was really the beginning of my career. I knew I did not want to be an American author and soon after headed off to cover the war in Afghanistan since I wanted to be a foreign reporter.

What was it like covering wars and being in areas of conflict around the world?

Being in danger is very scary, but there is an intensity and sense of meaning that comes from being in situations like that. I have been in several situations where I thought I may be killed, which is obviously an awful feeling. However, if you widen the context, you are in a critical situation that you are reporting on which is an important role and gives you a sense of meaning and purpose.

This can make ordinary life, which for me was being back in the U.S., seem bland and uninteresting, but of course it is not. There is nothing more meaningful than taking a walk in the park with your daughter, for example. However, at my age at the time, I felt that I had to prove myself. It took a long time in my life for me to reach the maturity to see the meaning in what many would refer to as mundane activities.

What are your views on war?

There are so many different types of wars. My father grew up in Europe and his father was Jewish so they fled Germany first in 1933 and then Spain in 1936 when the fascists came into Spain, and then France in 1940 when the fascists came into France. When I was growing up, war was the righteous counter to fascism. The moral choice was to confront fascism, even with violence if necessary. I was a kid during Vietnam, but this was a time when war became an immoral thing. After 9/11, it reversed again when the war was thought of as a moral and necessary thing. There was a legal and moral right to go after the terrorists.

Whether war is moral or immoral really depends on the context. While I covered the war in Afghanistan, I refused to cover the Iraq war because I felt it was immoral.

What were the factors that led you to stop being a war reporter?

My colleague and friend, Tim Hetherington, was killed on assignment during the Arab Spring in Libya. I was supposed to have been with him on that assignment, but at the last minute I could not go for a personal reason. My wife at that time and I got the call on our home phone in our New York City apartment alerting us of Tim’s death and she said to me that if I was going to keep going to these places of conflict around the world, she was going to spend the whole time worried that the phone was going to ring and the call would be about me, even if this was unlikely to happen. I realized that she was right and it was not fair to do this to her.

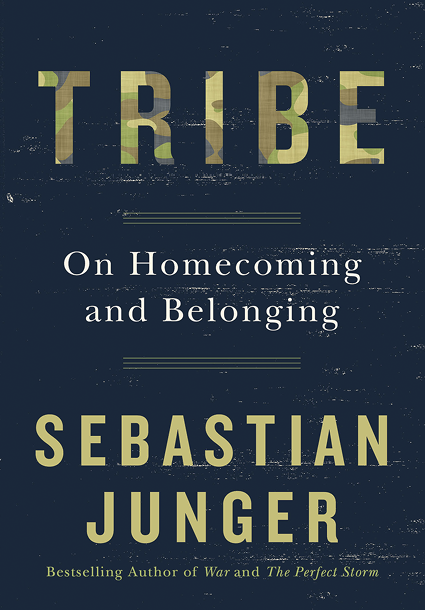

When I stopped, it was a difficult transition since it is a very easy identity which makes you very interesting at cocktail parties and in social settings – you are the war reporter. I had matured and realized that if that was the reason to not give it up, I had bigger problems. I was turning 50 years old at the time and it sent me on a more thoughtful path. If I had not made this change, my book, Tribe, would have never happened. It allowed me to go deeper into the human experience and was an enormously good thing.

What led you to write the book Tribe?

I had written a book called War and a reporter asked me why soldiers return from war so messed up. I gave a lot of thought to this question and realized that it was not that they were messed up – it was that they return and do not feel as if they fit into society, but in truth a lot of people feel that they do not fit into society. I thought about the incredibly strong fraternal bond in an adverse environment during war when the stakes are very high and everyone needs each other – this bond is our evolutionary past. You take these people from the suburbs and drop them into our evolutionary past, they respond very positively, and then you take them back out and put them into modern America which has incredibly high rates of depression, addiction and suicide – of course they are not going to feel good. In combat, it is a collective and the soldiers have community. This was the foundation for the book.

Photojournalist Tim Hetherington, who was killed

while covering the civil war in Libya in 2011,

with Sebastian Junger

What about your latest book, Freedom?

You are always looking for your next book, and after Tribe, I was thinking about what else people were willing to die for other than their family and community, and it is their freedom. Freedom is such a misused word and such an elusive word, and I wanted to write a book that was a discussion of freedom that no one has had before. For me, this meant how do less powerful groups maintain their autonomy and freedom in the face of more powerful groups. It is a very simple equation: if you are the biggest person in the room, of course you are free – everyone is afraid of you. But what about less powerful groups. I asked myself the question, “when have I been most free in life?” There are many ways to answer that – financial freedom, which I have now more than I had when I was a kid; temporal freedom, being able to do what you want with your time, which I have less now with responsibilities that I did not have as a kid – so it depends how you define freedom.

I thought one interesting definition was this: I had come up with a crazy idea and walked with a couple of veterans and a journalist along the railroad lines over the course of a year from Washington, DC to Philadelphia and then turned west to Pittsburgh. We chose the railroad lines because these are no man’s land, and it is quite safe and you can do what you want. We were sleeping in the woods, under bridges, and in abandoned buildings – we called it high speed vagrancy. I realized that most nights we were the only people who knew where we were – under what bridge, in what abandoned building – which was an important aspect of freedom. If people can’t locate you, they can’t tell you what to do.

I also realized like with any form of freedom, it only works if you agree to commit to other people to maintain your safety. You are not free from the group, because you need to be dependent on something – there is no such thing as complete freedom and complete safety. It is a balancing act between the freedom from an outside force, freedom from internal oppression, and commitment to the group to keep yourself alive and safe. I learned this during our experience since the four of us really needed each other to survive this tough environment. We could not have done it without everyone contributing to getting water, firewood, making food, carrying someone’s backpack when they were tired. That trip was what led to the book Freedom.

What are your views on isolation which is so prevalent in society today?

The more affluent the society, the more prone it is to isolation. I live in a middle to low-income neighborhood in New York City where there is subsidized housing and it is substantially Dominican and Puerto Rican. It is a tight-knit community. Everyone knows each other and is dependent on each other. It is possible to stay in socially healthier communities. I have spent a lot of time in Africa where kids do not have cell phones, and most adults do not have cell phones. I was in Liberia during the civil war, and we went back there when my eldest daughter was around three years old, and it was very peaceful. It was like a pre-technology society, and I remember telling my wife that if American society gets too alienated and dysfunctional, we could always move to Africa where life is actually more human. It would break my heart to do that because I love my country, but I do worry about the direction it is heading.

What are your views on what makes an effective leader?

I sometimes do speaking gigs for corporations where management wants me to discuss how you foster a feeling of tribe, which you can translate as loyalty to the company so that the company does better. They know that the feeling of loyalty increases production and improves results. I give a talk that I refer to as “battlefield lessons for the corporate world” where I try to distill down what I have learned. My focus is on saying something that is helpful in human terms and one of my messages is that you can lead a company, or you can manage a company. If you are going to lead a company, it means suffering the same consequences as everybody else. If there is a downturn, you personally experience a downturn. If you have to fire people because of a downturn, you do not get a bonus that year. Leaders do not take a bonus in a year when other people get fired. If you want to just manage your company, take a bonus, but don’t expect loyalty. Your people notice when only bad consequences come to them, and not to upper management.

Being a leader is about not thinking of yourself, but focusing on others. You are the last in the line. Real leaders see themselves as the last consideration in all the calculations they have to make.

One thing that I found when researching for my book Freedom is that the underdog groups that prevail tend to have a few things in common, and one of them is leaders that are willing to die for a cause – literally die for a cause.

+cover.png)

How did your health scare impact your views on life?

A few years ago, I had a pain in my abdomen which turned out to be a ruptured artery and within a few minutes I could not stand up. I was bleeding internally which can be a killer. It took me 90 minutes to get medical health and I barely made it. This incident really impacted me mentally as I am now very aware of my surroundings and knowing where the nearest hospital is and where medical care would be. I am always gaming things out, thinking about possible scenarios relating to medical issues. This is something soldiers are constantly doing in combat to make sure they are prepared for all possible scenarios.

This health scare was the hardest psychological struggle of my life, far worse than anything I experienced in combat. It went from a panic disorder to a real depression, and at that point I started talking to a therapist since I knew it was dangerous.

Do you have plans for your next book?

I am writing a book about what happened to me with my health scare. I’m an atheist and don’t believe in anything. While I was dying, my dead father appeared above me to welcome me to join him. I did not know at the time that I was close to death, but I actually was on my way out. The doctors were working on me when I saw a big, black pit open up underneath me and I was getting pulled into it. I was still conscious and talking to the doctors, but I could feel myself getting pulled into the pit and I didn’t want to go. I could see my father telling me it was okay and I didn’t need to fight it. I remember telling the doctors to hurry.

I am writing a book about this experience and about death, since I have a specific relationship with death having gone to war zones, and then after years of being in areas of conflict covering wars, having this health scare back home. I am trying to sort out all these thoughts and experiences in rational terms.

After having this medical emergency, it made me realize that none of us are guaranteed to make it to sundown. We are not living our lives with this knowledge – we live our lives assuming that we will make it to sunset. If you suddenly realize that you are living in a world where there is no guarantee, reality looks very different. If you can keep it from becoming too terrifying, it almost becomes sacred.

What has made it so important for you to not let success change you?

It is just not who I am. Nothing depresses me more than a nice Tribeca loft, because it doesn’t feel human. My family lives in an apartment that is less than 600 square feet – we co-sleep partly because there is not much room and there is no other space for the kids. Americans are the only mammal that does not sleep with their young. Every other animal, every other society, basically sleeps with their young.

Affluence depresses me. My wife and I do not fit into the culture of wealth and consumerism that seems to dominate today, which is probably why we are happy together. The push for affluence often leads to unhappy people and if you look at the numbers around depression, addiction, and anxiety today – this is clearly something this society needs to work on.![]()