- Home

- Media Kit

- Current Issue

- Past Issues

- Ad Specs-Submission

- Ad Print Settings

- Reprints (PDF)

- Photo Specifications (PDF)

- Contact Us

![]()

ONLINE

Nature-Based Solutions

Editors’ Note

Jennifer Morris is The Nature Conservancy’s Chief Executive Officer. For the past 25 years, she has dedicated her life to protecting the environment for people and nature. Almost 30 years ago, she was teaching in Namibia, with an eye on a career in public health. She then went on to receive a master’s degree in international affairs from Columbia University with a focus on business development and micro-finance. After a short stint at Women’s World Banking, she joined Conservation International. Morris was previously president at Conservation International, where she oversaw all programs across 29 countries and more than 600 million hectares of protected land. Prior to her role as president, she was the chief operating officer and oversaw significant growth in budget and staff. At CI she also worked on the conservation enterprise team, oversaw the Global Conservation Fund, and managed the Verde Ventures program whose business partners today employ nearly 60,000 local people in 14 countries with half a million hectares of important lands protected or restored. Morris has also led Conservation International’s Center for Environmental Leadership and Business, which partners with corporations to amplify conservation efforts and increase sustainability throughout supply chains.

Organization Brief

The Nature Conservancy (nature.org) is a global environmental nonprofit working to create a world where people and nature can thrive. Founded at its grassroots in the United States in 1951, The Nature Conservancy has grown to become one of the most effective and wide-reaching environmental organizations in the world. Thanks to more than a million members and the dedicated efforts of its diverse staff and more than 400 scientists, it is able to impact conservation in 79 countries and territories across six continents.

An aerial view of Clayoquot Sound on the west coast

of Vancouver Island in the Canadian province of British Columbia.

The Conservancy is conserving over 250,000 acres of old-growth

forest in partnership with local Indigenous communities,

doubling the area’s current protection. Clayoquot Sound is a

critical part of the 100 million acre Emerald Edge, the largest

and last intact coastal rainforest on Earth, whose majestic lands,

waters and wildlife are a global treasure of epic biodiversity

now struggling from threats to the environment in

coastal Washington, Alaska and British Columbia.

Will you provide an overview of The Nature Conservancy and how you define its mission?

The Nature Conservancy has been around since 1951 – we are celebrating our 69th birthday this October. For nearly seven decades, TNC has brought people together across geographies, backgrounds, ideologies and sectors around a common cause: nature. Our mission is to conserve the lands and waters on which all life depends, ultimately creating a world where people and nature thrive together. To accomplish this, we are focusing on the two areas where we think we can make the biggest difference: protecting healthy oceans, freshwater and lands, and climate change mitigation and adaptation.

Since our founding, TNC’s incredible network of staff, volunteer leaders, and generous donors have made it possible for TNC to protect more than 125 million acres/50.6 million hectares of land (bigger than the land area of Spain), conserve thousands of river miles, and develop more than 100 marine projects across America’s 50 states and dozens of countries and territories around the world. Our goal is to create a world where people and nature thrive together. We know that the actions we take today are important for protecting the natural world we rely on, and for charting on a more sustainable path for future generations.

How do you describe your leadership style and what do you see as the keys to effective leadership?

I’m a strong believer in the power of global, radical collaboration – both within an organization and in the broader environmental field. To me, effective leadership is inclusive leadership. It means bringing more people to the table, perhaps those who have been marginalized before or voices we don’t always agree with, to address environmental challenges in innovative ways. I do my best to practice humility and curiosity with my staff, and I ask other managers to do the same. This approach encourages people to listen for understanding, rather than listening to respond, and encourages teams to work together in ways they haven’t tried before.

Building this kind of inclusion and collaboration sometimes requires new structures, incentives, or other operational changes, and it might also require an even deeper culture shift. As a leader, my goal is to build trust between teams and colleagues so they are encouraged to collaborate, celebrate each other’s successes, and raise their sights beyond their own budgets and programs toward a shared vision.

Austin Laing-Herbert, Project Operations Coordinator

for Nature Seychelles, snorkels over the Cousin Island

Coral Reef Restoration Project in the

Cousin Island Special Reserve, Seychelles

How do you define resilience and what is the role of a conservation organization in building resilience?

As a conservation organization, we are especially excited about the role of nature-based solutions in building resilience, particularly in communities that stand to face the worst impacts of climate change, like extreme heat and more frequent and intense storms. Nature is one of the most powerful and cost-effective tools we have to create climate resilience for vulnerable communities. For example, salt marsh ecosystems which reduce wave height and energy during storms helped reduce losses up to 30 percent in some areas of the northeast U.S. impacted by Hurricane Sandy in 2012 and saved over $650 million in damage overall.

At the same time, these solutions also do so much more. Healthy natural systems (wetlands, grasslands, forests, etc.) store and absorb carbon – in fact, TNC’s scientists found that they can provide one-third of the emissions reductions needed to meet the Paris climate agreement’s goal for 2030. They also provide us with clean air and water, wildlife habitat, and places of recreation and inspiration.

Recent events, like the spread of COVID-19 from wildlife to humans and the resulting pandemic, are a clear wake-up call that protecting and restoring nature is more urgent than ever before. A recent study in Science demonstrated that protecting wildlife and forests would not only help prevent the spread of zoonotic diseases, but also cost just 2 percent of the estimated financial impacts from COVID-19.

As society rebuilds from the impacts of the global pandemic, we have the opportunity to invest in nature-based solutions that create jobs, stabilize economies and improve human health. For example, large-scale nature restoration efforts such as rebuilding wetlands or restoring degraded lands to natural forests have the potential to create as many as 40 jobs per every $1 million invested. During the 2009-2010 stimulus, every million dollars invested in ecosystem restoration created 10 times as many jobs as investments in traditional energy sectors.

What do you see as the importance of resilience in addressing the global crises the world is facing today?

Climate change is the biggest threat facing our world today. Impacts from the climate crisis threaten to undermine economies that depend on healthy natural resources, render entire cities uninhabitable from unmanageable heat waves, destroy coastal communities, increase the risk of zoonotic diseases, worsen the impacts of wildfires, and other horrific impacts.

Solutions to the climate crisis are about dramatically and urgently reducing greenhouse gas emissions. At the same time, these solutions must be about building resilience today so that we can survive the climate impacts we have locked in, and building resilience for the future so that we avoid further destruction. This is how we can put the world on a more sustainable path for our children and grandchildren.

I mentioned nature-based solutions earlier. They are a key component to building this kind of resilience. Important also is learning from and partnering with Indigenous Peoples and local communities who have been managing natural resources and stewarding lands since time immemorial. In Australia, The Nature Conservancy is partnering with Indigenous communities to improve grassland health, sequester carbon, and reduce the risk of wildfires like the devastating bushfires in early 2020. Through this program, Indigenous rangers in Australia set smaller, controlled burns to prevent the buildup of dry grasses that contribute to larger, hotter wildfires. These “controlled burns” draw on traditional knowledge dating back thousands of years before fire suppression policies and practices became the norm, and much of our fire work in the United States applies these same principles. This program contributes to healthier grasslands while generating income for Indigenous communities through the sale of carbon credits.

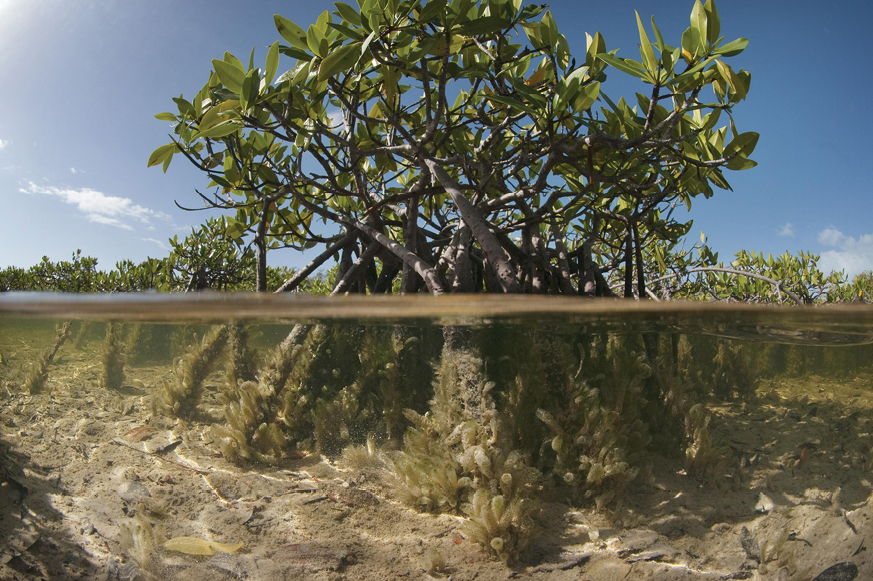

Mangrove in the shallow coastal salt flats of

Warderick Wells Cay in the Bahamas Exuma Cays Land

How critical is resilience to driving impact in non-profit work?

The nonprofit model has historically relied on generosity from donors and eligibility for government grants. These sources of funding remain incredibly important, but they are also limited, particularly in the face of an economic downturn when many donors and grantmakers are focused on crisis response efforts.

We know that our mission is more important now than ever before. That’s why we’re tapping into new sources of capital, like impact investment and debt restructuring, that can maximize the impact of traditional philanthropy to fund conservation that also supports local economies. One example of this work is Blue Bonds for Conservation, an approach which focuses on island and coastal nations who are particularly vulnerable to climate change and rely on healthy marine ecosystems for their local economies and protection from storms. Blue Bonds for Conservation leverages up-front philanthropy to restructure sovereign debt in exchange for a countries’ commitment to reinvest in natural resources by protecting as much as 30 percent or more of its near-shore ocean areas. The savings then helps the country create marine protected areas and fund conservation work that balances the needs of nature and people, leading to sustainable economic opportunities for all partners involved. In 2016, TNC worked with the Republic of Seychelles on this kind of debt restructure and to date the government has established marine protected areas twice the size of Great Britain.

With this approach, and with generous funding from philanthropists like Mackenzie Scott who donated $10 million in support of Blue Bonds in July 2020 to fund the teams, science and planning that turns a financial deal into a conservation success, TNC is now planning to work with as many as 20 island and coastal nations to refinance their national debt and unlock $1.6 billion for ocean conservation.

How has your work changed as a result of COVID-19 and the anti-racist movement across the U.S. and the world?

Pause, rethink, invest. This process applies to both interruptions from COVID-19 and the long-overdue reckoning with systemic racism in the environmental movement and unequitable experiences within our own organization.

The global pandemic has led to pausing field work in some places, arranging for virtual work for thousands of staff, and adapting advocacy strategies that hinged on long-planned events such as the Convention on Biological Diversity. Our goal is not to focus on how we can “return to normal,” but instead how we can continue advancing conservation priorities and science in our new and ever-changing reality.

In a similar vein, we are taking stock of TNC’s own participation in the systems and structures that have led to marginalizing Black, Indigenous Peoples, and People of Color across our history and our day-to-day work. I still have much to learn, and I’m grateful to the many courageous colleagues who have provided frank and direct counsel to me on these topics. As an organization, TNC has much to learn as well, and there’s a lot of work to be done to acknowledge past harm and be more inclusive. We’re taking steps now to build capacity around anti-racist work, improve our organization, and lift up partners who are doing essential work in environmental and racial justice. This will be a long process and we are dedicated to learning from experts and BIPOC colleagues on how to get this right.

Will The Nature Conservancy shift its strategy as a result of recent events and the advancing of global temperatures and more intense natural disasters?

We aren’t shifting our strategies, which have long focused on the impacts of climate change like rising temperatures and more frequent and intense storms, but we are doubling down on the areas where we can have the greatest impact. Now more than ever we see the urgency and importance of our mission. We are intensely focused on mitigation and adaptation in response to the climate crisis, and we will continue to be. At our core, we are a science-based organization, and we will continue to rely on the strongest science to inform our approach.

School of Gobblegut fish at TNC built shellfish reef at

Oyster Harbour, Albany, Western Australia. The oyster reef was

built

in November/December 2019. Today, a great variety of

marine life and fish can be seen around the reef.

As a leader, how are you able to build a resilient culture in your organization?

We are living through a moment where resilience is key to thriving, but it doesn’t look the same each day. As a working mom and the first permanent woman CEO of TNC, I can say with honesty and exhaustion that trying to parent and run a global nonprofit organization is hard. Some days are easier than others, but the realities of the COVID-19 pandemic have forced us all to face challenges that we did not anticipate.

When I am talking to colleagues about resilience and planning for the future, I tell them, “This is a marathon, not a sprint.” People come to work at TNC because the mission is important to them and the world is counting on us to do our part to create a more sustainable future for the next generations. This urgency and desire to do right by the world can sometimes lead to burn out. The added stress from the global pandemic which has upended our daily lives, relationships, and routines can put our teammates even more at risk. I encourage colleagues to take breaks, to experiment with flexible working arrangements, and to take care of themselves. Our Global Safety Director works closely with our operations and HR teams to ensure we have the resources and policies in place to help teams navigate this difficult time. Importantly, I also address managers directly, and ask that supervisors do their part in creating a culture where people have confidence that they can ask for help without fear.

The second important message is not to be afraid of failure. In our work, the stakes are high, but we must remember that failure is part of the scientific process. We need to know what doesn’t work, not just what does. Reframing failure as “learning” is critical to building resilience because it gives you the tools to get up and try again.

Do you feel that resilience is something a person is born with or can it be taught?

I think we are all born with the capacity for resilience, and that resilience is a skill that should be honed over time. I think about watching my daughter learn to walk for the first time – there was a lot more falling than walking for the first few weeks. These tumbles never really seem to phase babies and young children; it’s usually the parents who react with fear. As we get older, we start to fear falling. We start to worry that failing at something once means we’ll continue to fail over and over. Usually, that’s not the case. Practicing resilience means having the courage to try again, try new things, and be open to new relationships and ideas that can shine a light on a better way forward.

How has your personal resilience helped to drive your work?

I have always thrived on pushing myself out of my comfort zone. Reminding myself not to get too comfortable with any job or any mindset. We have to continuously be pushing ourselves to embrace a growth mindset which is for me the key to building lasting resiliency.![]()